Salzburg Festival doesn’t mess about. The offerings this year include an adaptation of Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain in Lithuanian, a Soviet-era operatic treatment of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, and Igor Levit tackling one of the Himalayan peaks of the piano rep. Kiddies, meanwhile, could enjoy the children’s opera Die Kluge (brilliantly done), a Nazi-era allegory on the rise of Hitler by Carl Orff, a composer they love here but whose politics are shall we say, um, complicated. (Pleasingly, I’m not sure the festival understands the concept of cancellation.) People always think Salzburg is pretty and fun. It’s not. It’s dark and primal, with a festival that is far more uncompromising and exhilarating than a global-elite bun-fight in provincial Austria has any right to be.

To play one of these works is to throw yourself off a cliff. To risk it all

The set-up is rather like at Mecca, with the daily worship taking place before a massive rock. The three main music halls – to which a quarter of a million visitors flock during the month-long summer Festspiele – are all carved out of the Mönchsberg, the looming clastic mound that dominates the city centre. In one of these, the Felsenreitschule – which once hosted blood sports and occasionally, when the Salzburgers decide to turn on a director, can summon up some of this spirit again – the back of the stage is the actual mountain face. To do pretty much anything in the old town, you have to navigate any number of caves. You park in caves, feast in caves, stroll through caves, listen in caves.

And inside the festival’s handsome lairs? Pure, mountain-fresh high art – remember that stuff? No disco nights. No gaming music. No ‘brat’ anything. Children have the Proms. Grown-ups head to Salzburg. Snob summer.

Take Igor Levit’s recital at the Grosses Festspielhaus. Rare, writhing Bach, introspective late Brahms and Liszt’s demonic arrangement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. It’s hard not to be moved by any pianist who decides to tackle a Liszt symphonic transcription, such is the likelihood that even the mightiest of techniques will be shown up by it. To play one of these works is to throw yourself off a cliff. To risk it all. Musical hara-kiri. An exercise in heroism and potentially total failure.

Levit leapt head-first into the meat-grinder. It was pure apex-predator stuff: rhythms were pounced on, runs devoured, sforzandi ravished. At the climax of the first movement, where the musical lines shoot off in half a dozen different directions, it felt like we were watching a famished big cat shredding its prey.

Not everything went Levit’s way. The Liszt managed to draw blood. But Levit was holding on. How? No clue. The speeds of his scherzo were certifiable, his finale deranged. And yet throughout this speed-demonry quiet miracles materialised: the distinct sound of flutes, bassoons, the avalanche-rumble of double basses, a resplendent halo of brass sound, all somehow emanating from the hammered strings.

There was no escaping the physical athleticism of all this. You could see it manifested in the bulging vein on the back of Levit’s neck. Salzburg was hosting an Olympic event too, it seemed. There was also no escaping Levit’s fury at the end. After 45 minutes of staggering pianism, everything tumbling thrillingly to the conclusion, disaster struck. He botched his landing – fluffed the final attack in the last bar. A red mist descended. Before his encore – a milky rendition of the C-sharp minor Chopin nocturne, the perfect digestif – he showed us what it was meant to sound like. What kind of pianist fesses up to a mistake to their audience? A true great was before us – or possibly a madman.

What kind of pianist fesses up to a mistake? A true great was before us – or possibly a madman

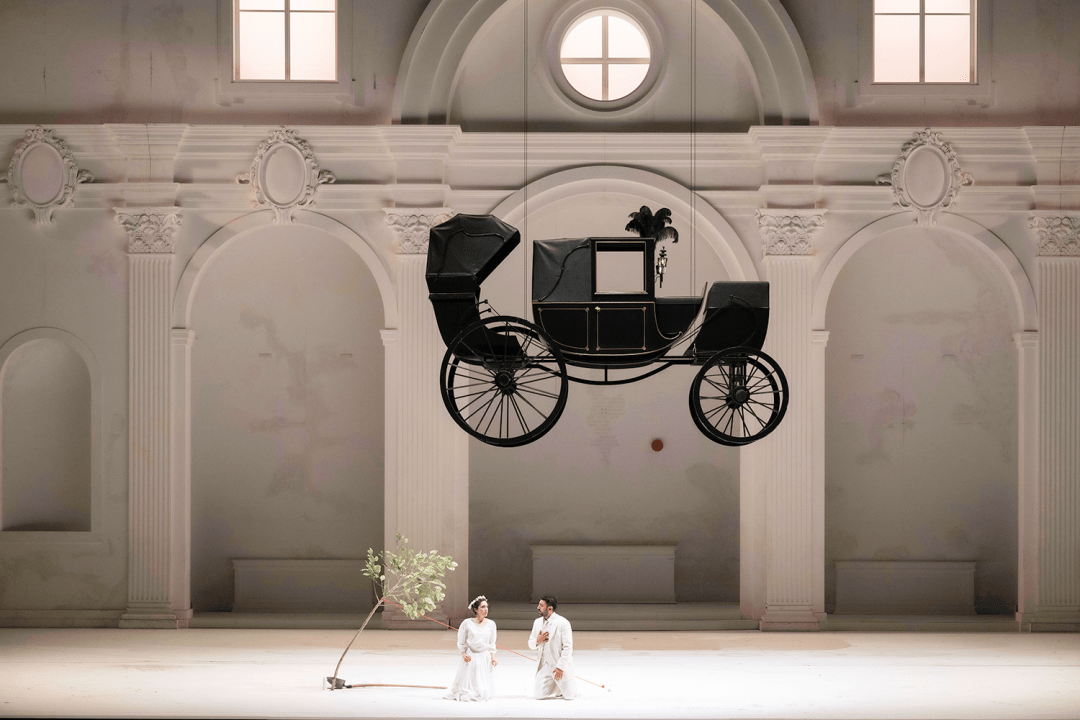

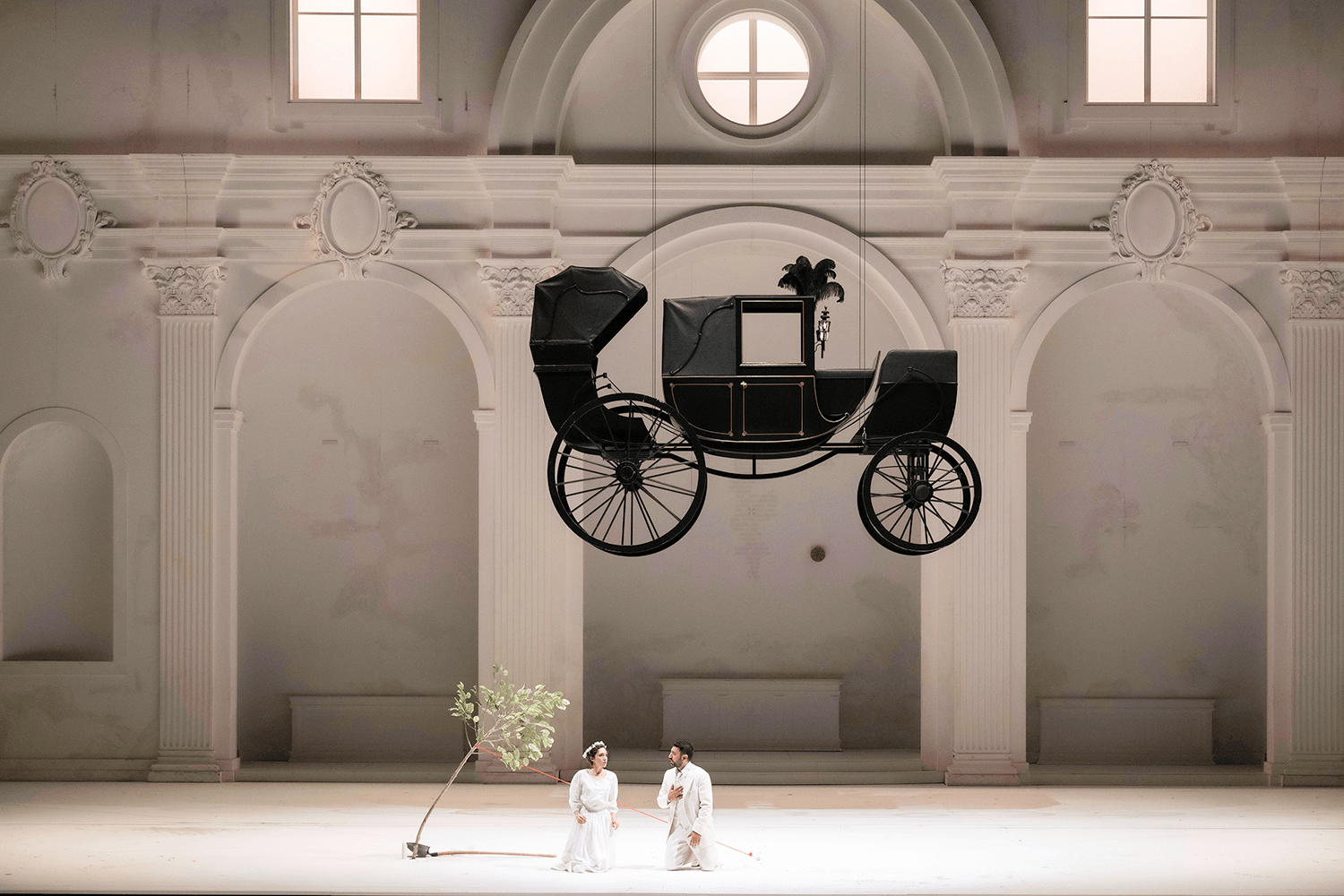

The next night the same stage offered up more greatness and madness and primal mystery. Romeo Castellucci was having another go at Don Giovanni, with Teodor Currentzis back in the pit, this time with his Utopia Orchestra. What had changed? Well, the Audi car, that in the 2021 production was dramatically dropped from the heavens like a bomb, was spared the same fate this time. But the grand piano wasn’t – and you felt the thud.

Beyond that we were in familiar Castellucci territory. Forget what most directors aim for: the usual tight weave of music, meaning and drama. What Castellucci trades in is startling tableaux vivants. Here’s a goat. Here’s some marionettes getting jiggy. Here’s Zerlina being bound, shibari style. Here’s two photocopiers kissing. It’s oblique and disjointed and pretentious, no doubt, but often indelible, a constellation of flickering symbols, hinting at meaning. Sliced backhands all night. But then clarity would suddenly strike. A witchy mass of women would appear, backlit, violently thrashing their hair in nightmarish silhouette, and chills would shoot down the spine; or Currentzis would emit a fusillade of sulphur from the pit and silence all doubts.

But doubts there were. With all energy invested in the aesthetic lightning flashes, choreography and characterisation were too often left to engage in cliché. Here was Don Giovanni, the complete slimeball; Donna Elvira, the bore; Don Ottavio, the simp. Massed extras, meanwhile, floated about in Barbara Cartland pink representing some kind of universal feminine. The voices could have saved things but only Nadezhda Pavlova’s Donna Anna attempted to match the searing quality of the stage visions.

Ultimately I’m not sure operatic Mozart suits the mystical-conceptual Castellucci treatment. (The boos from the audience suggested they didn’t either.) The musculature of the drama, the dynamic potential of the relationships: to not flex these is a terrific waste. A great Don Giovanni-Leporello match-up can often provide enough fuel to power an entire production. Here, they barely seemed to know each other.

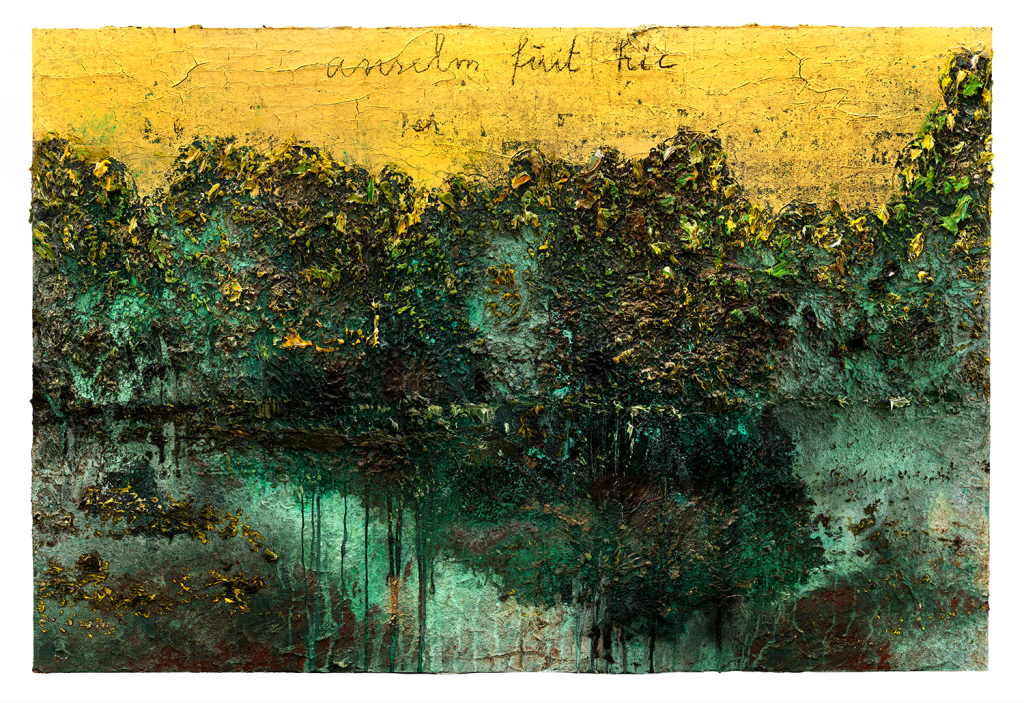

Thanks to Salzburg gallerist Thaddaeus Ropac, the visual arts always put on a decent showing during festival season. At his Mirabellplatz site, I parked my nose a few centimetres from Anselm Kiefer’s new canvases. You can do this in a private gallery. They trust you. Step into one of these billionaire showrooms and you cease to be a member of the public. You’re presumed at once to be a connoisseur.

Art theorist Maurice Merleau-Ponty believed there was an optimal distance from which to view every painting. Inspecting Kiefer’s 13 new oils it struck me that I had found the ideal position: within licking distance. Move back any further and one quickly became mugged by sentiment and association. They became mere pictures back here: legible visions of Kiefer’s memories of the murky green Rhine as a child, the banks lined with bowed trees, the sky crowned by blinding sunsets. Pretty, generalised, genteel and second-hand. A hint of Klimt, a nod to Monet, a wink to Watteau. ‘Anselm fuit hic’, it says, graffitied at the top of many of them. ‘Anselm was here’: viewed from the middle distance the paintings are all past tense.

Bury your face in the works, however, and the present tense of the paint wildly working itself out over the canvas returns. Here, amid the linseed oil fumes, every violent eddy and gyration becomes tangible, every ocean floor scar a mini thriller.

Follow the Kiefer hand as he conjures up whorls, boils and blisters. Allow yourself to be ensnared by the fiery licks, claggy swamps – thick as cupcake icing – and cracked mud. And look at that sticky green-black stalactite of oil paint slowly making its way to the floor. The microscopic allows for no gentility. No nostalgic revisionism. Even the gold-leaf sunbursts sting up close. There was no oasis down here from which to reflect, just endless fire. Not pretty, not fun – but all the more exciting as art.

Comments