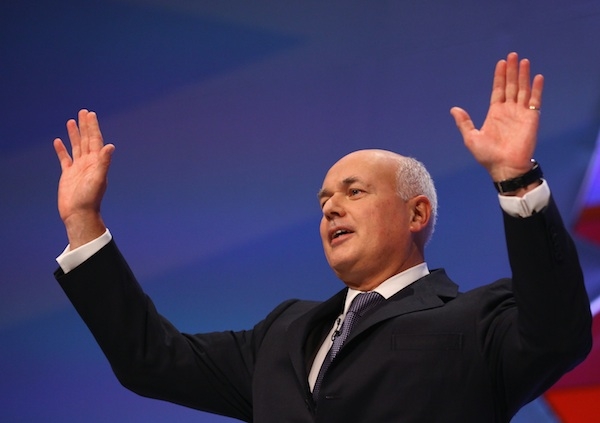

For some time we have known about the tension between George Osborne and Iain Duncan Smith over welfare reform. The Chancellor wanted more welfare cuts, and the Work and Pensions Secretary resisted: real reform, he said, would cost money. So far, so understandable. But a new biography of the Chancellor by Janan Ganesh reveals another element behind the struggle. Ganesh writes that Osborne ‘questioned the analytical rigour of the Christian Conservatives who hovered behind the project’. A Treasury source is quoted making it clearer still: ‘He thinks the people pushing this are such total advocates and evangelicals that they blind themselves to any downsides.’

To put it another way, the Christianity of Mr Duncan Smith and his associates makes them suspect. As ‘evangelicals’, they don’t function intellectually the way that others do. That’s new. Until very recently, politicians and pundits regarded Christianity as a system of beliefs and values. Grown-ups might have doctrinal differences, but Christianity was a respectable and rational foundation for a world view. When Lady T rowed with bishops, she dealt with them on their own scriptural terms, saying that the Good Samaritan had to make money to give it away in the first place. Religion was part of public debate, not an impediment to it.

It would be unfair to suggest that Mr Osborne’s reservations about religion in public life are anything but typical. The writer Matthew Parris recently expressed exactly the same kind of reserve, with his characteristic charm and eloquence. He recalled a discussion in which he listened respectfully to the arguments of one anti-abortion MP — until he smelt a rat. ‘I noticed his surname. It struck me he was probably a Roman Catholic. I checked; he was a notably convinced Roman Catholic.’ So Parris concluded that the argument was a smokescreen. ‘He presumably believes that it isn’t really a matter of x weeks or y weeks but that almost any termination after conception is not just a sin but a mortal sin, punishable by eternal damnation.’

In other words, the Catholic MP — who had, I assume, an Irish-sounding surname like my own — could be safely discounted as a rational player in an important debate because ‘presumably’ he’s got a thing about sin and damnation. Anyone who lives in parts of the UK still blighted by sectarianism will recognise this way of thinking. But to hear it raised in an English context is quite new.

What bothers me is the underlying assumption that not just Catholics but religious people generally are incapable of arguing from first principles, because they’re indoctrinated. I am a Catholic, and no one would charge me with keeping the fact quiet. I am also anti-abortion, but not because of scripture. Not because of ideas about when a foetus acquires a soul. Not because the Pope tells me to be. I’m anti-abortion because I regard the foetus as a human entity — a view derived from biology — which should have some protection in law.

I suppose that this viewpoint is, at heart, religious, but I find it is shared by quite a few atheists and agnostics. I can’t, in all honesty, distinguish my views on this subject from those, say, of Dominic Lawson, an atheist from a Jewish cultural background. Or from those of the late Christopher Hitchens, who was a pro-lifer in his way. Or from any atheist who believes that life is sacred, and that this life begins some way before birth. To claim that concern about abortion is the preserve of the religious is, in its way, a slander on agnostics and atheists. The idea of Catholics having a secret allegiance to the Pope is a familiar, stubborn trope in British history. But what’s new is that this analysis now applies to all ‘people of faith’. And it is creating, in some quarters, a view that religion is a bias that ought to be declared. Perhaps in an official register.

When Evan Harris headed the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee, he felt that expert witnesses should declare their religious affiliation before giving their opinions. In 2009 the World Association of Medical Editors took this into an academic context, and said that editors of medical journals should require contributors to declare any interests that might affect their views. Yes, but which views? Patricia Casey, a professor of psychiatry at University College Dublin, wrote a commentary in 2008 on a paper about the effects of abortion on mental health for the British Journal of Psychiatry. She was promptly taken to task for not declaring her Catholicism — yet some of her critics had themselves undeclared interests as abortion providers. The authors of a recent paper on abortion and mental health, funded by the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, didn’t feel obliged to say that the foundation was also biased: it was ideologically pro-choice. But crucially, it’s religious belief that appears to undermine the validity of your research and your academic integrity. Secular prejudice doesn’t count.

It’s an extraordinarily offensive assumption that people convinced of a political persuasion can be seen as rational, as long as they don’t go to church, mosque or synagogue. And if they are religious, it is to be assumed that their options are dictated to them by a priest, rabbi or imam. In America, where churchgoing levels are still quite high, things are different. An interesting aspect of the vice-presidential debate between Paul Ryan and Joe Biden was that it was between practising Catholics. Their take on politics could hardly be more different but both declared without embarrassment that they were influenced by their religion. Paul Ryan said his pro-life approach is ‘not simply because of my Catholic faith… but it’s also because of reason and science’. Joe Biden said he shared the same position on abortion, but declined to impose it on others. Two Catholics, two views. It happens.

But Joe Biden went further than any British politician would. ‘My religion defines who I am,’ he said. ‘And it has particularly informed my social doctrine. Catholic social doctrine talks about taking care of those who can’t take care of themselves. People who need help.’ It’s quite possible that Duncan Smith would make the same argument. But does that make him politically suspect?

That’s the thing: religion does indeed affect our moral outlook. But, if anything, it’s in the direction of compassion and justice. It means having a thing about the poor. Yet you’d get short shrift from secularists if you prefaced every policy about wanting to diminish poverty and help the vulnerable with the declaration of interest that you are a person of faith. Religion has an agenda all right: it’s about being your brother’s keeper. I don’t think, though, that it’s what the secularist lobby has in mind.

Comments