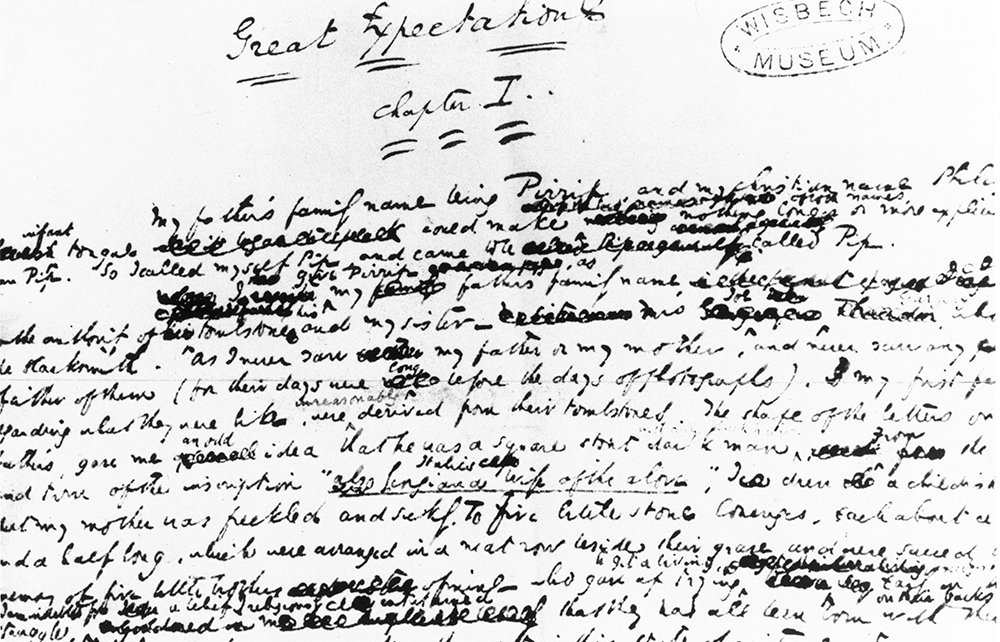

‘Can you read Dickens’s handwriting?’ asked a blogger. Underneath was a picture of his manuscript for chapter 23 of Oliver Twist. It looked easy enough to read: ‘If the village had been beautiful at first it was now in the full slow and luxuriance of its richness.’

No, slow couldn’t be right. Must be flow. But no. The published text tells me it is ‘full glow and luxuriance’. I should have seen it the first time, for even in one paragraph of Dickens’s writing, it is obvious that he made his gs like a descending s or a barless f. When a g was joined to the preceding letter, he would carry the stroke up and into a tight anticlockwise loop, then plunge down to make the tail. Forming letters is a thing we do half-consciously, and consistency of habit makes our handwriting recognisable, or it did when we all wrote every day.

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in