Like most prime ministers, Boris Johnson has grown fond of deploying the military — albeit so far on the home front. Enthused by the army’s service in the London Olympics, he turned to them when the pandemic struck and 101 Logistic Brigade have been embedded in government ever since. They distributed PPE to frontline workers in March last year, and this year have become an integral part of the vaccine rollout. ‘The military don’t moan about health and safety regulation or a 40-hour week,’ says one minister. ‘Everything just works.’

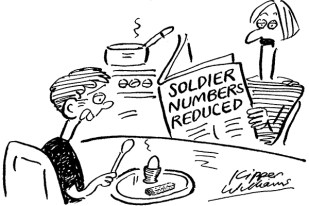

The future of the military was this week laid out in a blueprint billed as the biggest strategic rethink for a generation. This is normally Whitehall code for huge cuts, but what’s strange this time is that the defence budget is about to have its biggest rise since the end of the Cold War. Though the army is still shrinking, the thinking behind this is not so much to break from the cycle of recent failure, but from a cycle of pretence: from the myths politicians tell themselves — and the public — about what the army can do.

Ben Wallace is the first Defence Secretary for decades to have served in the army. He left the Scots Guards for politics just as Tony Blair’s wars got underway. Britain ran into battle behind America, but with a fraction of its resources — and I saw the consequences for myself shortly after the invasion of Iraq. Britain pretended to take charge of Basra, the second city. We failed, leaving a security vacuum which was soon filled by Shi’ite death squads. Barbers were executed for shaving beards and Basra’s morgues filled up with the mutilated bodies of women accused of un-Islamic activity.

When Des Browne was defence secretary, he arranged a photoshoot with the governor of Basra to show the world that the city was safe.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in