Counter-insurgency operations, as any army officer could tell you, are a messy business in which the consequences of failure are always easier to measure and appreciate than the rewards of victory. Moreover, even limited success in one area – the destruction of the enemy’s ‘human resources’, for instance – can be offset by the manner in which that success is achieved. Short-term success cannot be confused with long-term stability. And therein lies one of many paradoxes: counter-insurgency operations frequently involve starting fires to put out other, larger, fires.

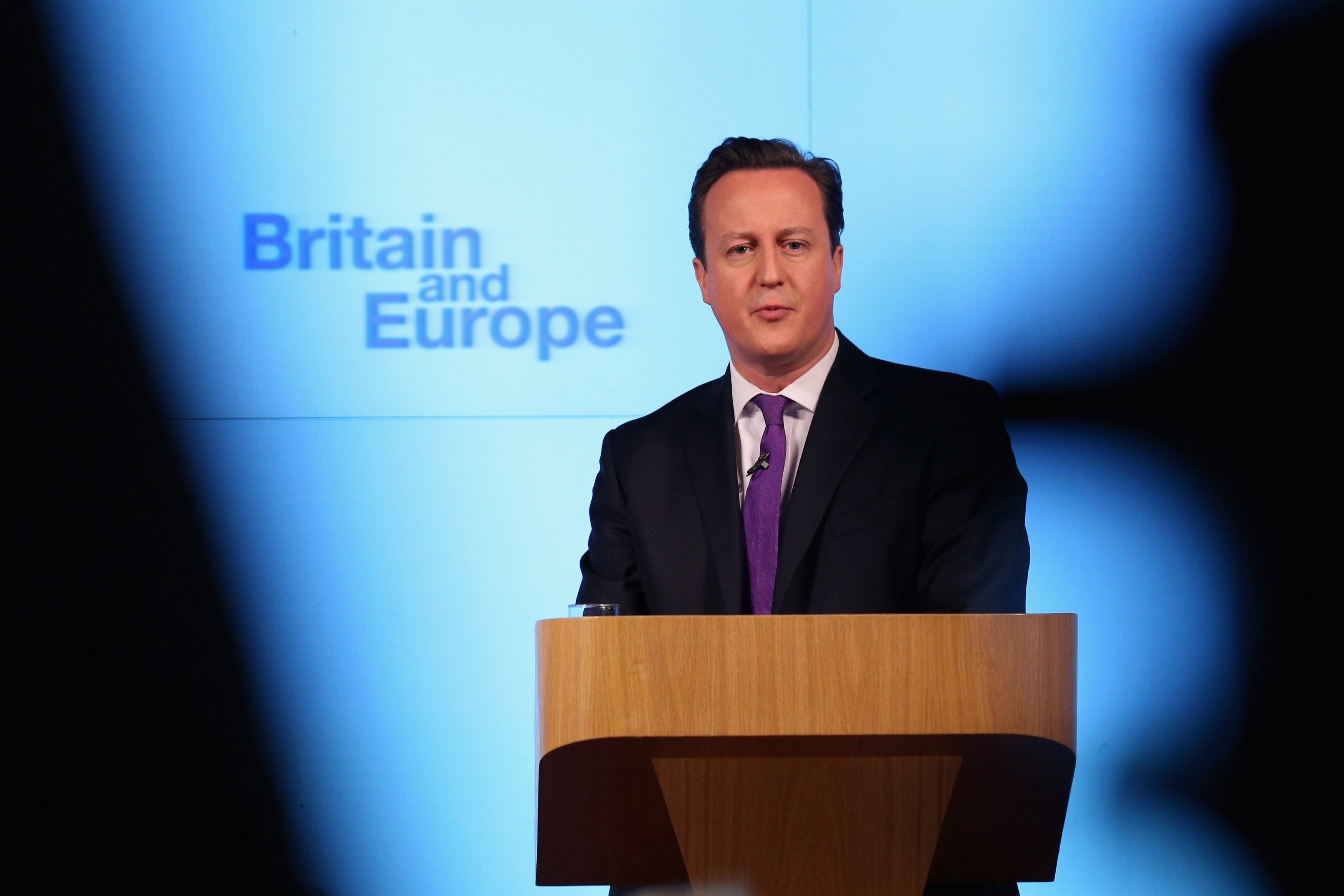

Politics, as David Cameron might now tell you, is often much the same. The Prime Minister is, this week, fighting twin insurgencies. Each threatens his position, his authority, and his potential legacy. In each instance, he finds himself having to pacify a vocal minority without, he hopes, angering the so-called ‘silent majority’ upon whose judgement his success – or failure – ultimately rests.

The problems of Scotland and Brussels are more similar than sometimes supposed.

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in