William Kentridge’s work has a way of sticking in the mind. I can remember all my brief encounters with it, from my first delighted sight of one of his charcoal-drawn animations, ‘Monument’ (1990), in the Whitechapel’s 2004 exhibition Faces in the Crowd to my awestruck confrontation with his eight-channel video installation I am not me, the horse is not mine (2008) in Tate Modern’s Tanks in 2012. That marked a high point for the Tanks, since when they’ve tanked.

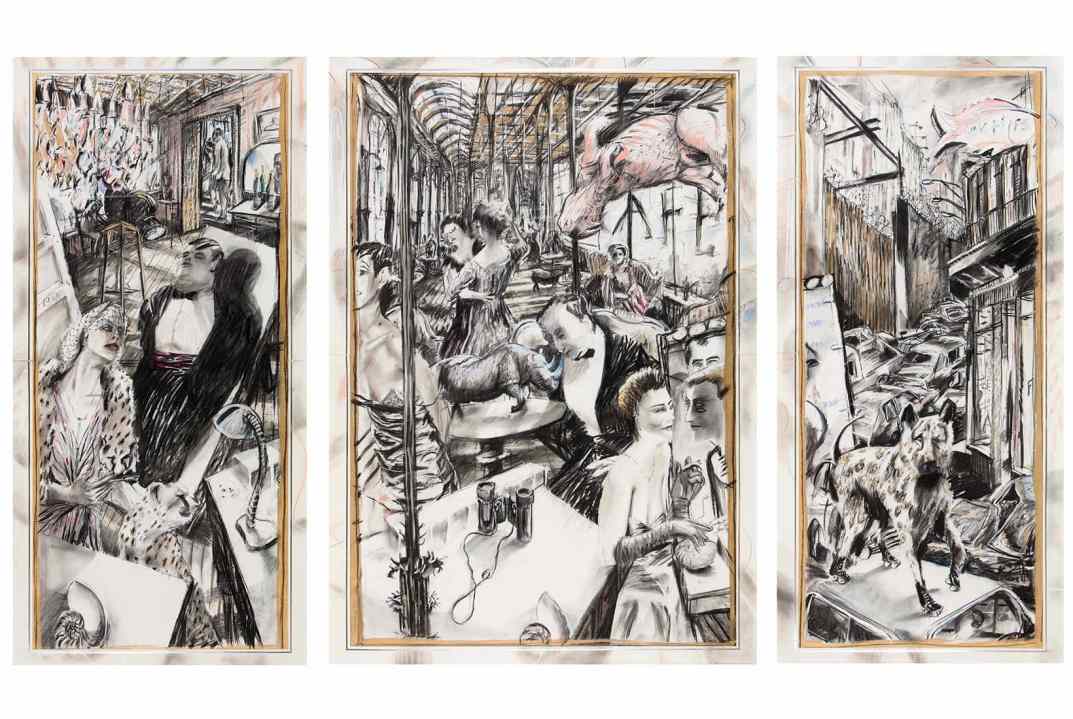

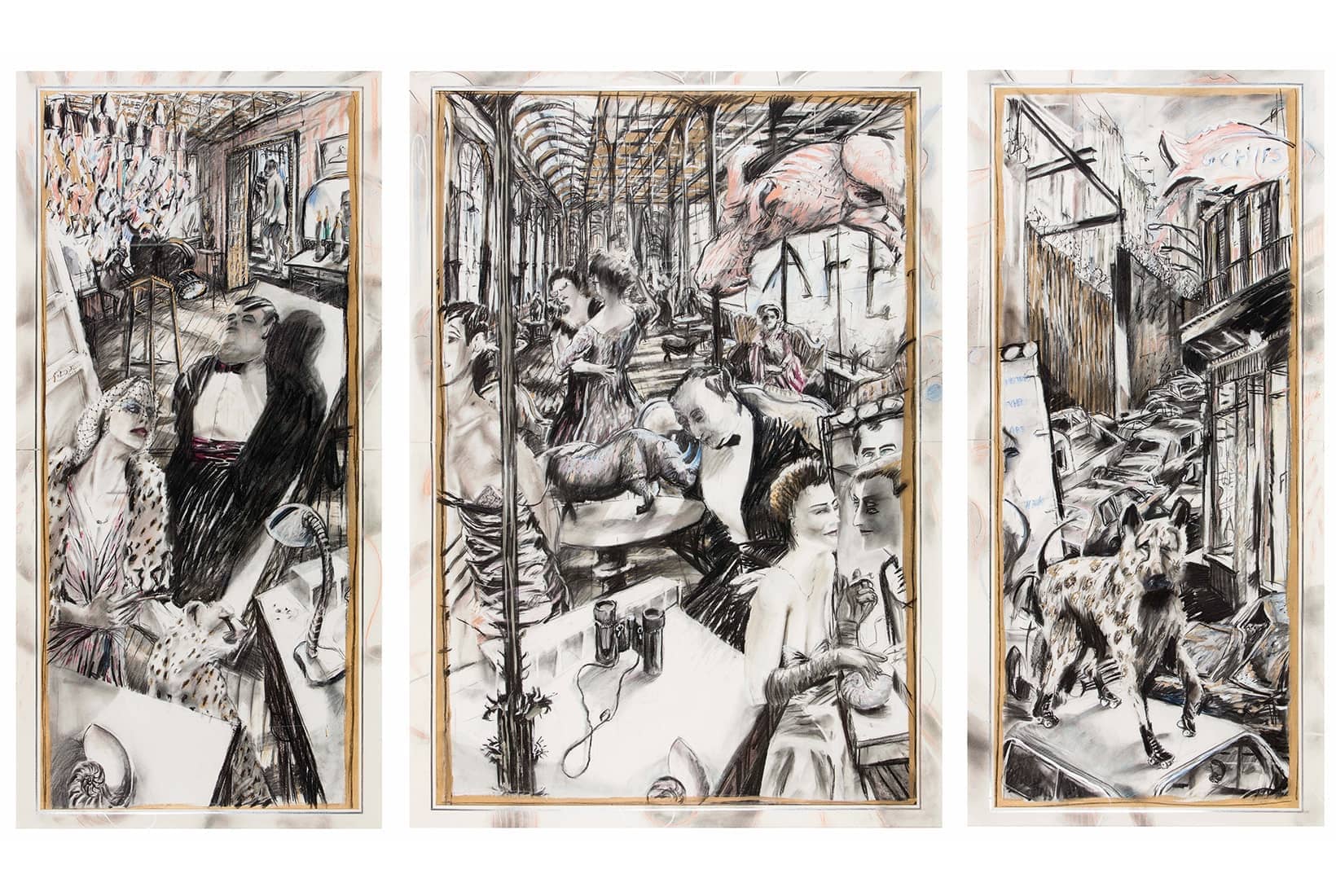

Kentridge’s is a face you don’t forget, partly because it often appears in his own animations in the guise of his beaky alter ego Soho Eckstein, partly because of the trademark vintage props – megaphones, projectors, Moka coffee makers – and oompah-band soundtracks that accompany his films. But in the 1990s, when his work first reached these shores, it stood out from the crowd for another reason: it was out of key with contemporary British conceptualism. It was ironic, yes, but the irony had a different timbre; echoing Beckmann, Grosz and Dix and Bertolt Brecht, it seemed to belong to an earlier era of northern European cultural history.

Kentridge’s work seemed to belong to an earlier era of northern European cultural history

Where had Kentridge sprung from? South Africa. The son of two anti-apartheid lawyers – his father Sydney Kentridge represented the family of Steve Biko – he grew up under apartheid in a country forcibly stuck in the past, a world away from the peace, prosperity and blurred moral lines of post-war Europe. It was a place of constant state surveillance and brutal oppression, but also of clear-cut contrasts between truth and falsehood, poverty and plenty, black and white. Like the Weimar Republic, it proved a stimulating climate for radical art.

There’s almost no colour in the Royal Academy’s 40-year retrospective of Kentridge’s work; it’s all black and white or smudgy shades of charcoal in between.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in