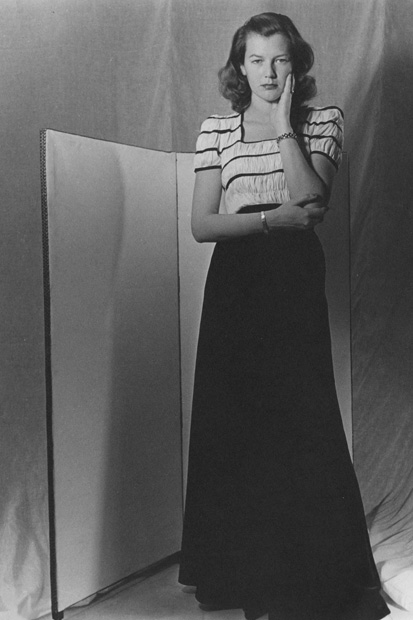

Around 200 Englishwomen lived through the German Occupation of Paris. Nicholas Shakespeare’s aunt Priscilla was one. Men in the street stopped to gaze at this blonde with the careless allure and raw beauty of Grace Kelly. Some fell instantly in love.

Her second mother-in-law thought her face showed truth and sincerity, and the reader shares this impression of integrity under duress. She was a reckless driver, yet was also shy, gentle and biddable. She had a beguiling habit of stroking your arm to show affection. She was not vain.

Born in 1916, hers was a rackety childhood. Her self-engrossed parents, imprisoned within a failed marriage, then in new partnerships, rejected her. Her stepfather imposed a tariff that licensed — in return for each Latin lesson — his shoving his hand up her skirt. She often woke screaming from nightmares. She escaped to study dance in Paris until osteomyelitis forced her to stop; and six years later she returned there with only a borrowed £5 note, pregnant by a feckless South African.

In Paris she suffered a dirty abortion, vividly and horribly evoked, risking her life. But Vicomte Robert Doynel, 17 years her senior, had seen her and undergone a coup-de-foudre. Robert rescued, wooed, and smuggled her into his family château in Normandy full of largely unsympathetic relatives. Starved of parental love, she was ignorant about desire too. Marriage seemed finally to offer an escape from this sad, cruel childhood. But Robert continued to treat her as a child, never soliciting her views or advice. Moreover, she very much wanted children, and he was impotent.

The book springs into intenser life as the war approaches. There is much of interest about the state of divorce laws in the 1930s; there are arresting Parisian brothel scenes; and above all else there is Occupied France.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in