Peter Mandelson’s famous quote about New Labour being intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich has a suffix that is often mischievously omitted: he added ‘so long as they pay their taxes’.

But there are a few more things which many Labour members would have put on the end: so long as you don’t earn it by advising Central Asian dictatorships, so long as you don’t hang around with Russian oligarchs, so long as you don’t make it from the Saudis.

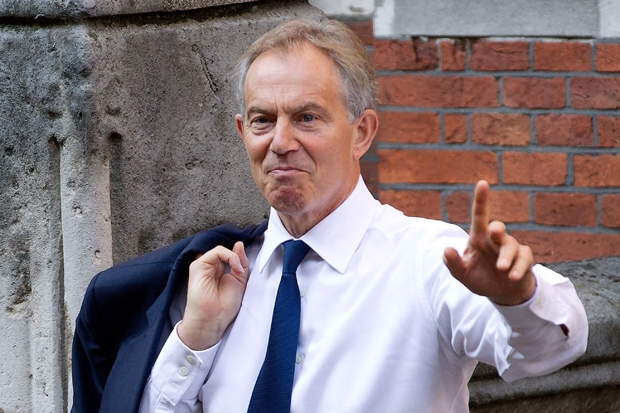

Tony Blair and Peter Mandelson got filthy rich all right. But the whiff they gave off while doing so has only served to regenerate a very Old Labour disgust of wealth. This week, Peter Mandelson became the latest Labour figure to criticise Ed Balls’s mansion tax, calling it ‘crude’ and ‘short-termist’. The issue threatens to spark a Labour civil war over envy politics and wealth. The painstaking efforts of Tony Blair to turn his party from a socialist one to a socially democratic one, to convince the faithful that profit is not a dirty word but the source of the tax revenues which pay for social programmes, are in danger of ultimately showing for nothing.

In Ed’s Labour, profit once again seems to be something you bring in on your shoe. The default position is anti-business: enterprise is a problem which has to be contained, not the lifeblood of the economy. Miliband has no one with business experience, just lawyers and professional politicians.

For Tony Blair, it is a case of all that hard work — gone. All those aspirational voters frightened away again. He must have felt some sadness as he predicted, in a recent interview, that the coming election would be one where ‘a traditional left-wing party competes with a traditional right-wing party, with the traditional result’.

But then he might reflect that he shares some of the blame for the turnaround in Labour’s attitude to wealth. Imagine that you are a young Labour activist still forming your opinions, trying to reconcile grubby capitalism with socialist ideals and find your personal third way. There are lots of enterprises which you might identify with as combining profit with a sense of what Blair used to call ‘social justice’. You might be drawn to social media, for example: no workers or animals harmed in that. Or you might look to green energy: who would begrudge a small fortune to someone who comes up with a practical way to slash carbon emissions? Or ethical tourism, or a fair-trade supermarket.

What probably won’t feature in your idea of the acceptable face of capitalism is Tony Blair Associates, not with its £8 million in fees from advising Kazakhstan dictator Nursultan Nazarbeyev. You will balk even more to learn that Blair, a great champion of efforts to combat climate change, is raking it in from the oil industry; not only that, but through ventures with autocratic governments in Azerbaijan and Saudi Arabia.

What especially offends about Blair’s new career as a roving adviser to some of the world’s least democratic governments is the sense that he is exploiting contacts which he made as prime minister. There is a provision by which former prime ministers must clear business interests with parliamentary authorities, but it only lasts two years.

Blair may argue that, now the period is up, he is as entitled to make hay as any other citizen. But then if he considers himself just another private citizen, why is he still claiming a £115,000 a year allowance to help him fulfil his duties as a former prime minister? He wants to rid himself of all constraints and yet still enjoy the trappings of his former office. That is having your Kazakhstani fried honey cake and eating it.

It is as if Edward Heath had gone on to make a mint in the international panda trade, or Jim Callaghan had gone off to promote the Mustique tourist business. No one has found anything illegal in what Blair is up to, but somehow it still doesn’t seem right.

If I were a Kazakhstan taxpayer I think I would feel still less impressed. Blair has forged a career in a profession which he helped to create: that of the highly paid outside consultant to government. His business is not quite private sector and not quite public sector but in a strange nowhereland between the two. Think of all those council executives, all those NHS managers who left with large pay-offs and then appeared back, as consultants at thousands a day, in what looked remarkably like their old jobs.

No wonder Labour’s faithful have once again taken against private enterprise. The man who tried so hard to sell it to them has gone on to espouse one of its less attractive sides: private enrichment from public administration, and from dictatorships to boot.

Comments