Arriving in Blackpool by train is just as I’d always dreamed. At the Pleasure Beach station, I disembarked right by the roller coasters, which rear up like Welsh hills beside you and, with the seagulls, welcome you with shrieking riders and clattering wheels. There are vast coasters in wood and metal weaving in and out of each other. Curvaceous and sprawling, they’re Gina Lollobrigida in steel.

I’ve wanted to visit Blackpool for years. Spending my early childhood near Clacton-on-Sea, I got used to the delights of a tacky seaside town, and Blackpool is surely the mother of them all – even if it’s a mother with too much blusher and mascara on, who looks as though she’d scratch your eyes out if provoked. The town as we know it was constructed in the second half of the 19th century, with its three piers, trams and famous Eiffel-inspired Tower (at 518 feet, it was then the highest structure in the British Empire). Blackpool still attracts over 20 million visitors a year. If she’s gaudy and vulgar – a ‘great, roaring, spangled beast,’ as author J.B. Priestley called her – no one is complaining.

I found a childish inner voice urging me to put off my journey home and do it all over again

As I walked down the Golden Mile, the seafront promenade, it didn’t disappoint. From the South Pier, crammed with moving rides, Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ echoed out ghostly over the Irish Sea. It was an overcast autumn day and the whole of the town seemed touched with a sulphurous yellow light. There are old-fashioned joke shops selling hand-buzzers and stink bombs (‘If you can’t take a joke, don’t come in!’) and fortune-tellers’ booths where there are seers and ball-gazers. There are endless boarding houses with names like ‘Chimes of the Sea’ or ‘Viking Hotel – Talk of the Coast’, and banners outside advertising events. ‘Enjoy an evening with Steve Davis… snooker superstar. Get ready for an evening filled with laughs, cheeky banter, and loads of audience interaction. It’s going to be a cue-tastic time!’

But it’s when I got to Central Pier that the full Blackpool effect hit me, along with the smell of deep-fried donuts and the stench of molten onions. There are casinos, bingo halls, gin palaces, oyster rooms and a seafront wedding chapel. More fish and chip shops than I knew existed (called things like ‘Mother Hubbard’s Famous Chips since 1972’ or ‘Greedy Zaks, Burgers, Dogs and Donuts’) and that sell more tonnes of fried potatoes than I thought growable, in more ways than I thought feasible. ‘Cheesy fries’, ‘bacon-loaded fries’, ‘crispy onion-loaded fries’, ‘chilli-loaded fries’, ‘jalapeno fries’, ‘curly fries’ and, rather disappointingly, just ‘fries’. Sticks of Blackpool rock are on sale in flavours like ‘Blue Raspberry’, ‘Iron Brew’ or ‘Ganja’, and waffles come stacked high with different, glutinous toppings. Sometimes the Golden Mile seems like the biggest furred artery in the world. Blackpool is ‘tacky,’ admitted the actor David Thewlis, who grew up here. ‘But I love it for that… People come here to get away and be thoroughly bad… to eat far too much, drink far too much, smoke far too much, have far too much sex and bad weather.’ Everything about Blackpool, he said, is ‘cheap and nasty. I’m proud of that cheapness.’

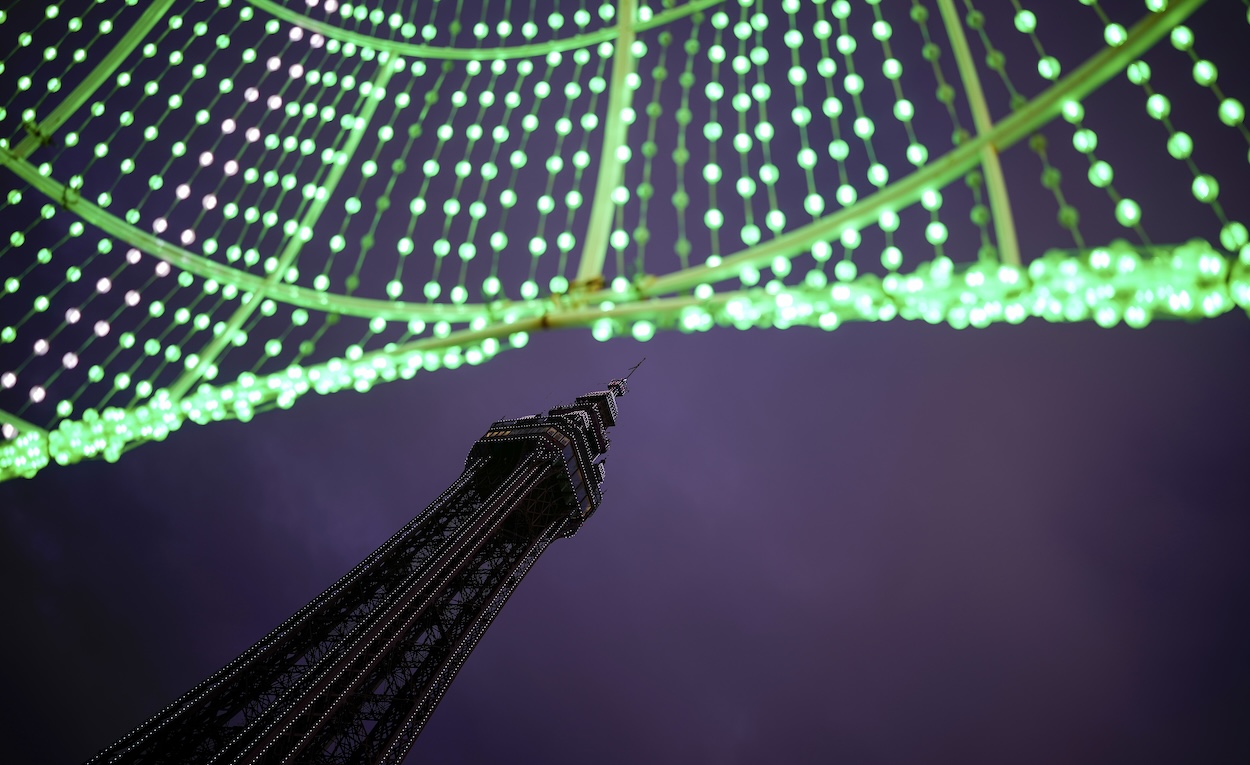

Certainly, it isn’t dull for a moment. Ferocious-looking bald men strode past with pitbulls, some of their faces so heavily tattooed they look like a different ethnicity. Everywhere I saw families – sometimes three generations – linking arms or sticking doggedly in groups: this, after all, is their time together. A caped old man with a stick trudged past, seemingly a war veteran, but his sole medal read ‘Paranormal Research Centre UK’. Everyone was vaping, even the pensioners, whose mobility scooters left a storm-cloud of flavoured steam behind them, like little locomotives. Evening came and more people emerged, the famous illuminations glowing above them, the Tower lit up in different colours. Stalls sold luminous swords, plastic guns and windmills, lights flashing, their ends spurting out a wave of soap bubbles.

The North Pier, a little way on, advertised forthcoming shows like ‘Totally Tina!’ (a Turner tribute act) or ‘It’s Simply Comedy – Roy Chubby Brown.’ Nearby, there’s an area called the ‘Comedy Carpet’ paved with thousands of comedians’ catchphrases (‘Get your titters out!’ ‘Give us a twirl!’) and things like the naughty lyrics of George Formby’s ‘Little Stick of Blackpool Rock’:

I lived guiltlessly, for three days, on burgers, hot dogs and donuts, spending two nights in a one-night hotel, sleeping in a lower bunk. The mattress directly above me had a large, apparently permanent brown stain about halfway down and all night there were the sounds of angry gulls and drunk tourists outside.

The second day, I went to the Pleasure Beach – in the last week of its annual season – to try the roller coasters. There are about ten of them there, both old and cutting edge, but it’s the ‘Big One’ I wanted to ride first. On its opening in 1994, with its 205-foot drop and 74 mph speeds, it was the tallest and steepest roller coaster in the world (though now, with ‘Hyperia’ at Thorpe Park, it’s not even the tallest in the UK). The Big One dominates the landscape at Blackpool, the town’s great, metal mountain, and naturally there was a long queue. While we waited, we chatted and watched others ahead of us scooting back down the rails, the ride over for them. They looked shaky and slightly manic, but elated (it’s a look I once saw on the face of a Yorkshire terrier in Andalucía, clinging for dear life to the shoulder of a speeding Vespa rider). By the time we’d reached the front of the queue and were climbing into the cars, we were so relieved to be sitting down again that all fear had gone.

Actually, the ‘Big One’, after 30 years of waiting, is a slight disappointment. Yes, the initial journey up its endless chain lift is stomach-churning, as is that first, near-vertical drop or the hill you soar up afterwards. But modern coasters tend to be smooth and gliding. However fast they go or however tight the corners they fling you round, you feel you’re essentially in good, loving hands.

For a truly hair-raising time, you need to go on the older, wooden coasters, made for a generation which had withstood the first world war. Blackpool’s wooden coasters, the ‘Big Dipper,’ the ‘Grand National,’ the ‘Nickelodeon Streak,’ all built in the 1920s and 1930s, are deliberately terrifying, bouncing you brutally up and down, hurling you violently from side to side. Two of them are listed buildings. They’re rides from a time when corporal punishment was still allowed in schools. I came off them shaken, bruised, slightly chastened – and wanting to repeat the experience.

Walking back to the station on my final morning, past the donut stands and underneath the roller coasters, I found a childish inner voice urging me to put off my journey home and do it all over again. I didn’t of course – I’m in my fifties now and know better – but maybe I should have done. Blackpool had given me way too much and, like so many of its departing visitors, I wanted more. ‘No one’s too humble to come to Blackpool, and no one’s too sophisticated,’ said Geoffrey Thompson, the Pleasure Beach’s late owner. ‘They just come.’

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in