Art is a fundamentally childish activity: painters dream up images and sculptors play with stuff. It was while playing with an inflatable ball with her young daughter in the early 1960s that Maria Bartuszova had the idea of filling balloons with liquid plaster instead of air. The inspiration fed her muse for 30 years, seeding the mixed crop of biomorphic forms currently filling five rooms at Tate Modern.

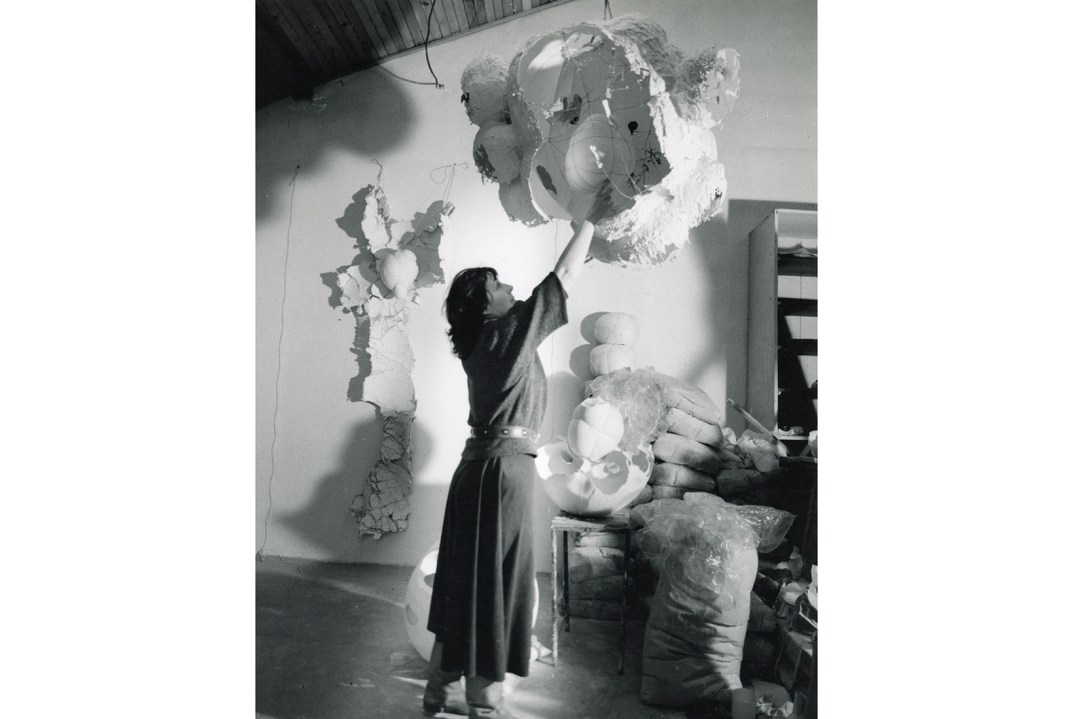

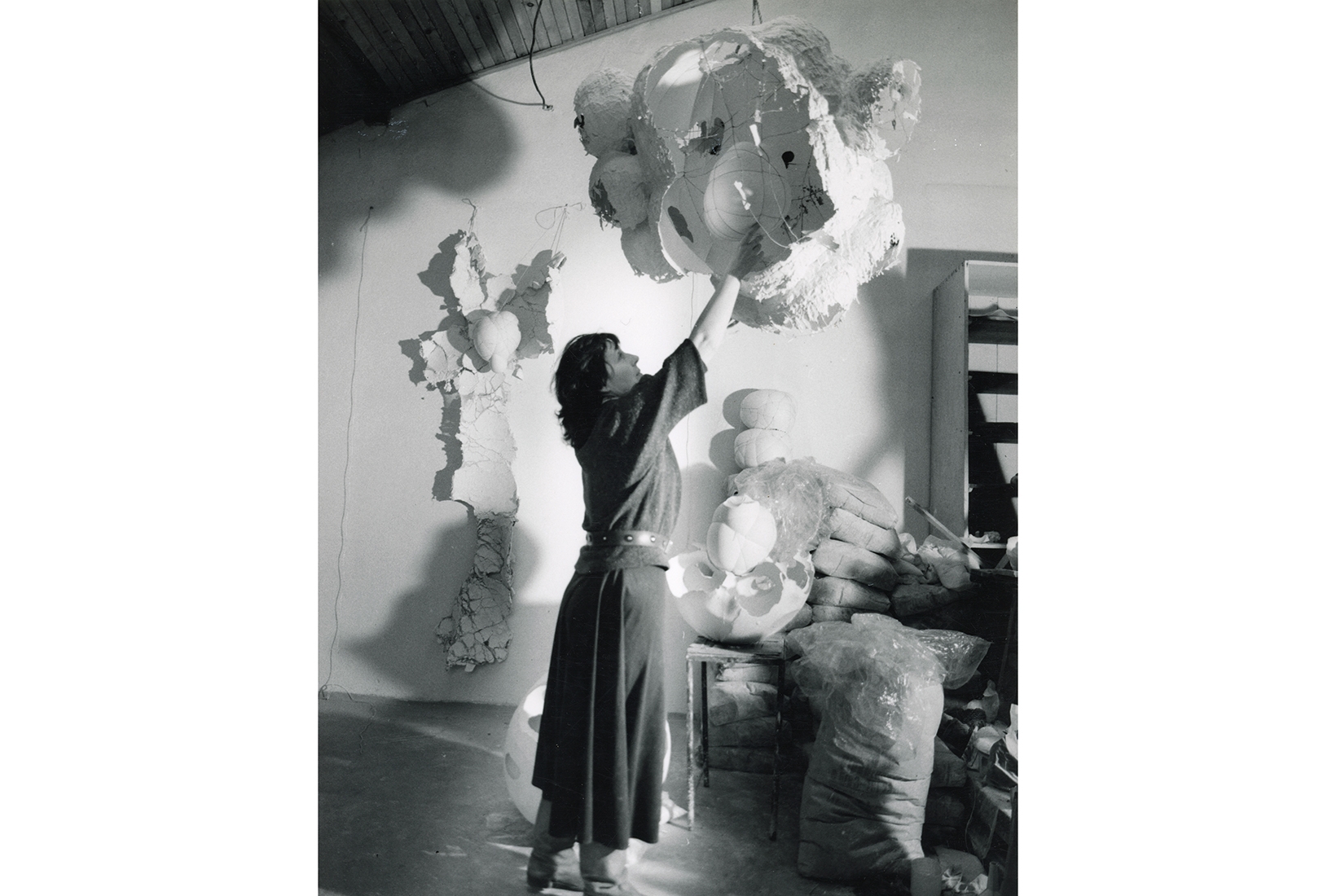

Trained in ceramics at Prague Academy of Arts under communism, Bartuszova turned to plaster after moving with her sculptor husband Juraj Bartusz to the industrial city of Kosice, now in Slovakia, in 1963. Plaster was cheap and plentiful: a 1987 photo in this exhibition, the first to bring her work to a British audience, shows her with stacks of sacks of it in the studio. The natural forms she initially cast from it – raindrops, wheat grains, eggs, germinating buds and dividing cells – feel pregnant with life. She called the process ‘gravistimulation’, manipulating the gypsum as it set, sometimes underwater to counter the effects of gravity. Malleable, squidgy, dimpled by the sculptor’s hand, suspended like caciocavallo cheeses, bound with cord like Nobuyoshi Araki nudes or twisted into intestinal coils like Sarah Lucas’s ‘Nuds’ made of stuffed tights, the forms are not just palpable, they’re palpatable – they tempt the viewer to cop a quick feel. To Bartuszova, an enlarged grain of wheat is as inviting as Mae West’s lips in a Dali sofa. There are other echoes of the human body: incompletely inflated balloons terminate in nipples and wrinkly knots recall other parts of the anatomy. Some forms have unforeseen associations: to a contemporary eye, the models for her two-part sculpture, ‘Metamorphosis’ (1982), for Kosice crematorium look like oozing cheeseburgers.

Malleable, squidgy, dimpled by the sculptor’s hand, Bartuszova’s forms tempt the viewer to cop a quick feel

In the 1980s, now divorced, Bartuszova developed a negative casting method she called ‘pneumatic’; rather than filling balloons, she inflated them before coating them with plaster, stripping the rubber to leave a fragile shell.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in