Back when Radio 4’s Thought for the Day was original and insightful, Lionel Blue was a regular source of rabbinical wisdom and dodgy jokes. Sometimes he’d come up with a phrase, a concept, that let you see the world in an entirely new way. One certainly changed how I see politics: his notion of ‘moral long-sightedness’. The ability to see and get worked up about problems thousands of miles away or a hundred years’ hence, while failing to see the scandal under one’s own nose.

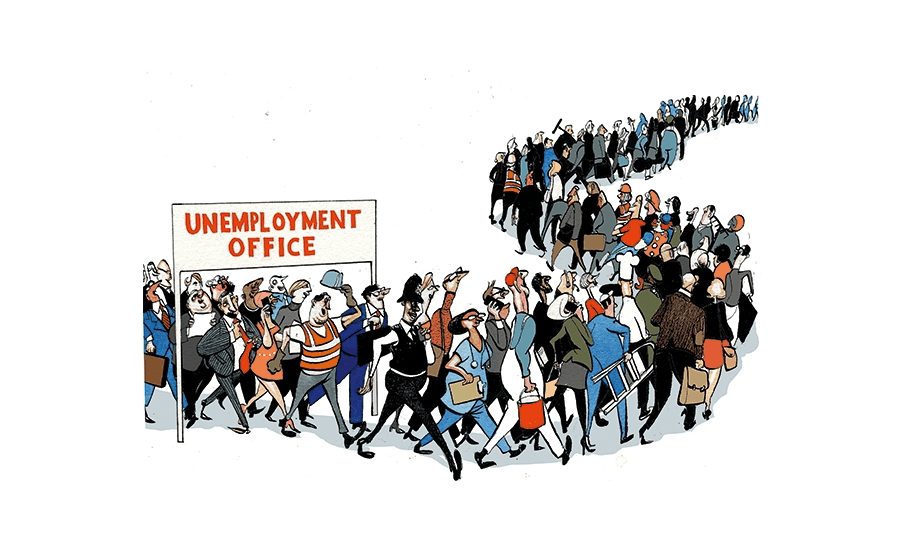

It sums up the indifference over welfare. It’s in crisis, with 4,000 claiming sickness benefit every day. Worklessness scars our great cities: in Manchester, 18 per cent are on out-of-work benefits. In Glasgow and Liverpool it’s 20 per cent, in Middlesborough 22 per cent and Blackpool 25 per cent – figures that would be scandalous in a depression but this is in the middle of a worker shortage crisis. The costs surge every year. Britain has somehow succeeded in making the most expensive poverty in the world.

In short, the rise of mental health complaints has discombobulated the welfare system with high numbers being sent to the economic scrap heap deemed unable to do any work. It’s now at almost 40,000 a month:

The last pre-Budget report proposed a crackdown on conditionality which I regarded too little, too late. But was I being too mean? This is now assessed by the Office for Budget Responsibility but it takes a few weeks for this to feed through into the DWP caseload forecast, one of the most important documents to not be reported. The update was released before Christmas and it shows that the disability benefit caseload is expected to rise by an average of 920 a day for the next five years.

The previous forecast envisaged just over 1,000 a day, so Mel Stride's reforms do make a difference. But a small one. This remains a full-blown crisis that will have to be dealt with by whoever wins the next general election because of the financial cost: so big that it’s measured as a share of GDP rather than in mere billions.

The DWP analysis has plenty more to say, laying out the human and economic cost of welfare dysfunction. In every dimension: it's a proper horror story. But no one seems to care. This indifference has a human effect. For as long as the welfare crisis is not really controversial or is mentioned in the Commons, people will keep being shovelled off to live in edge-of-town estates as eager, well-trained immigrants take their place in the workplace. To me, the immigration issue is not so much the supply but the demand. The problem is the vacuum in the labour market created by heavy taxes and dysfunctional welfare.

And no, this isn't about lazy Brits. Just before lockdown, the share of UK workforce in work or looking for it had hit a record high: the reforms of Ian Duncan Smith had worked. This is what made Rishi Sunak confident about furlough: he thought that the UK now knew how to move people back to work. This proved tragically incorrect: the UK ended up the only country in Europe to have fewer in work now than before the pandemic. This has also passed without comment. A shame, because there are many lessons to learn. The IDS welfare reform was about moving people from benefits into work: the puzzle now is how to handle mental health complaints.

This is not just a story of the over-50s not going back to work. This is also about the young, who are now registering long-term illness on a scale that we have never seen before:

I’m not sure how much bigger this problem needs to become before it is a political talking point. Mel Stride does care, as does Jeremy Hunt. But fixing this properly would mean picking a battle that Sunak does not – politically – have to fight. Not, at least, for as long as no one is talking about the problem. All three men may want to throw everything they have at this issue, but all three know that there would be no political capital in this fight. So why do so before a general election? When no one is really calling for it?

We’ll continue to highlight this at The Spectator and the welfare section of our data hub will bring regular updates. It is, in my view, the most important topic in politics and if I was guest-editing the Today programme I’d devote all three hours to it. Interview people making claims, talk to the DWP officers assessing them, the Blackpool employers trying to find workers in a city where one in four is on out-of-work benefits. And then GPs who are asked to sign sick notes, who could explain why it's so difficult – under the current system – to avoid sending people to the benefits trap.

This is fixable, as the 2010-20 reforms showed. But first, people need to start talking about it. Let's hope this happens in 2024.

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in