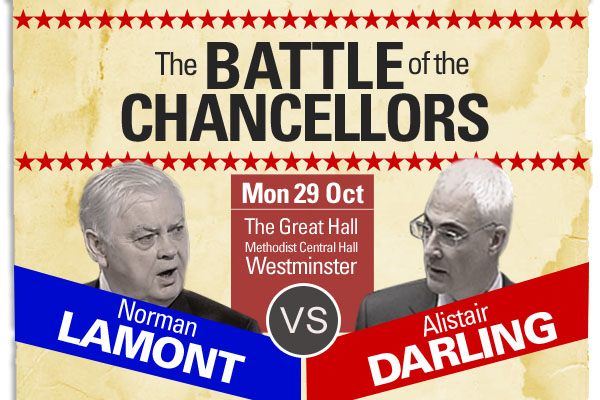

Nearly a third of the audience at last night’s Spectator Battle of the Chancellors debate arrived not knowing whether George Osborne’s plan was working or whether a plan B was in order. It was all to play for, and the six speakers attacked the task with quite some gusto. Former Labour Chancellor Alistair Darling kicked off the debate by looking back to his own time in the Treasury, telling the audience that this was a crisis of the banking system by using an alarming anecdote of a conversation with a senior banker in the midst of the 2008 crisis.

‘He said, “I just want to give you some confidence, some reassurance: my board met last night and we agreed from now on we will only take risks we understand.”‘

Darling contrasted his own response to the crisis – ‘back in 2009, our economy was growing and it grew right into 2010’ – with the government’s approach, arguing that ‘austerity on its own isn’t working: we have not got growth’. The government ‘has to step in when the private sector won’t’, he said, arguing that public spending should be cut once the growth had returned, not beforehand.

But Tory MP Jesse Norman, opposing the motion ‘George Osborne isn’t working: we need a Plan B’, congratulated Darling for ‘his attempts to rein in’ Gordon Brown, and disputed the idea that the crisis had come purely from the banks. While supporting the chancellor’s plan as ‘absolutely the right one to take’, Norman’s speech was not a cheery one, saying this kind of recession will take of the order of six or 10 years to come out of, adding that he wouldn’t expect a return to proper, healthy growth before 2014 or 2018.

Former Liberal Democrat Treasury spokesman Lord Oakeshott took a rather dim view of Norman’s picture of the economy, teasing him that it wouldn’t sell well at the ballot box in 2015. He attacked the banks and said the coalition agreement hadn’t delivered on its first promise for the ‘banking system to serve business, not the other way round’.

Instead of arguing for a Plan B, Oakeshott pushed for a Plan C.

‘What we need instead is a far bolder plan for economic recovery. I call it Plan C for construction and capital investment rather than a Plan B, but we can all agree at least, on this side of the debate, that Osborne isn’t working. We must be mad to treat our record low long-term interest rates as some sort of virility symbol, instead of an unrepeatable opportunity to finance desperately-needed investment.’

But what would Alistair Darling’s Plan B have looked like? ‘We do not have to guess what he would have done,’ said Spectator editor Fraser Nelson. ‘Because he told us.’ He pointed to Darling’s April 2010 budget in which the plans the then Labour Chancellor had made for dealing with the economy were not so strikingly different to those followed by George Osborne when the coalition formed. ‘Let’s not pretend [George Osborne] is some savage cutter: he’s cutting by less than one per cent more’ than Darling, said Nelson. He later warned that ‘George Osborne has not covered himself in glory… he’s dealing with the debt in the same way that the late George Best dealt with the drink: by having more and more of it’.

Ex-Monetary Policy Committee member David Blanchflower talked the audience through a series of slides which showed this was ‘the worst recovery’. He said:

‘Plan A has demonstrably failed, this is the worst recovery in 100 years, now is the time to act because it will only get worse and it will hurt the young.’

He also criticised the Conservatives for talking the economy down from the start and damaging market confidence in Britain’s economic prospects.

Those proposing the motion for a Plan B talked about increasing public expenditure to stimulate growth, and they were joined briefly by former Conservative chancellor Norman Lamont. He supported the idea of a stimulus ‘if we started off from a point of strong public finances’. But he was ‘not sure by any means’ that this applied to Britain’s current financial situation. Like his two fellow speakers opposing the motion, he pointed to the fact that ‘this crisis began in 2007’.

When the floor opened up to questions, the first speaker asked why there had been such scant mention of quantitative easing. While Blanchflower predicted that the MPC would be likely to vote for more rounds of QE, Darling questioned whether this would continue to have a positive effect. And what would happen once the QE programme was over? ‘The answer is they do not have a clue,’ said Nelson, adding that there was a risk that ‘this recovery will turn out to be a QE-fuelled illusion’.

While those against changing course supported the idea of further supply-side reform to get the economy moving, Blanchflower was scathing: ‘There’s no evidence to actually support it,’ he argued, claiming that higher levels employment protection often correlated with a more healthy economy.

The debate lasted two hours. When those at the sell-out event crowded in to the hall, they voted 105 for Plan B, 133 against and 112 said they did not know. By the end of the debate, there was a clear winner: 154 supported Plan B, and 250 voted against a change of course.

Comments