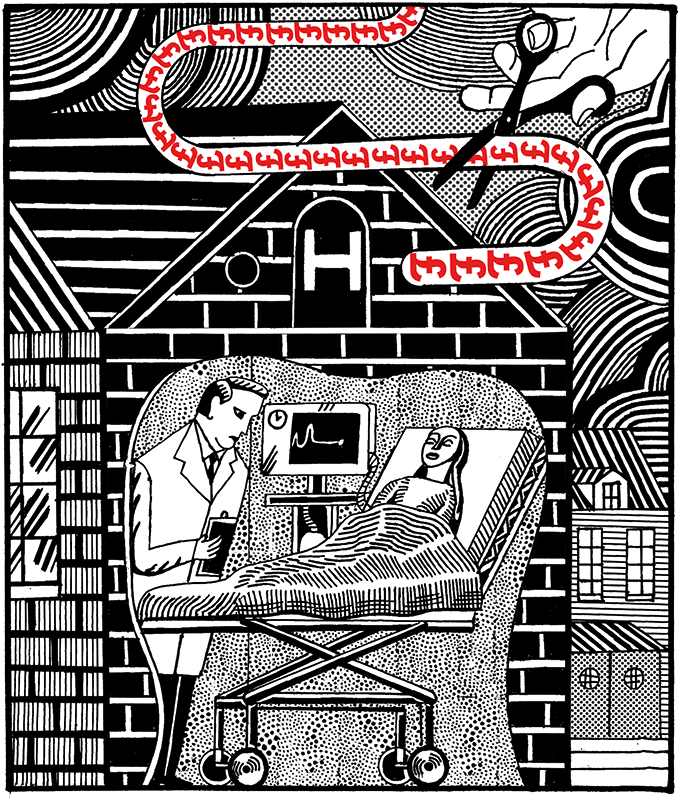

The hospice movement is one of the great achievements of post-war Britain. Inspired by the doctor Cicely Saunders, who in effect founded the field of palliative care, it has united cutting-edge research with a profound understanding of suffering and how to relieve it. Britain’s hundreds of hospices are Saunders’s legacy.

But can that legacy survive an assisted suicide law? ‘It has the potential to destroy the sector in its entirety,’ says Amy Proffitt, former president of the Association for Palliative Medicine (APM). If assisted suicide is integrated into palliative care, and hospices legally must facilitate it, then ‘many of the medical profession would leave the sector entirely’, Proffitt adds. Dr Dominic Whitehouse, a consultant at a Sussex hospice speaking in a personal capacity, tells me the bill would be ‘the death knell’ for hospices.

‘This could be the end of hospice care as we know it. I would resign before being involved’

Under Kim Leadbeater’s bill, which faces a decisive Commons vote this month, doctors can decline involvement. But hospices and care homes cannot opt out. That has major implications. ‘Hospices are generally quite small places,’ says a consultant at one London hospice. ‘It’s not something you can just have in a corner.’ A doctor at a Yorkshire hospice adds: ‘If you are the only consultant in the hospice for a week, you will be present and you have a duty of care.’

‘This could be the end of hospice care as we know it,’ a consultant at a Welsh hospice says. ‘I would resign before being involved. Many others feel similarly.’ A consultant at a different hospice in Wales told me: ‘I can think of multiple staff who would leave… Senior medics wouldn’t want to be involved.’ Speaking to staff across 17 adult hospices – one-tenth of the total in England and Wales – I repeatedly heard similar sentiments.

Patients may also steer clear. A common refrain from hospice workers is that the bill will transform the image of hospices from sanctuaries of care into houses of death. ‘Overnight we will see a steep decline in people wanting to come in,’ says one consultant. ‘It’s going to be a lot harder to convince people their grandparent wasn’t euthanised with a syringe driver when we’ve also been doing… just that.’ Another former APM president agrees with Proffitt’s warning about the destruction of the sector. ‘Medics will find other work,’ they tell me. ‘You’ll see a collapse in palliative care.’

Donors might also be put off (‘I’ve been afraid to ask the charitable foundation that funds us what they think,’ says one medical director). While public funding only covers 30 per cent of palliative care, it could become dependent on hospices’ willingness to provide lethal drugs.

For the bill’s proponents, this probably sounds melodramatic. Why can’t doctors, who specialise in relieving suffering, make lethal drugs an occasional addition to their toolkit? For Leadbeater, palliative care is ‘not in competition’ with assisted suicide.

But that misunderstands how the sector’s professionals view their work. Saunders – an opponent of assisted suicide – laid down the meaning of palliative care: ‘You matter because you are you. You matter to the last moment of your life, and we will do all we can to help you not only to diepeacefully, but also to live until you die.’

Those words, one consultant at a Midlands hospice tells me, are ‘the foundation of the hospice movement. Everything is geared towards that.’ With assisted suicide, ‘we’re saying a certain kind of life is not worth struggling for. That will create a huge tension.’

Palliative care aims to mitigate not just physical symptoms, but also psychological, emotional and existential distress. Dr Mark Lee, a consultant at a Sunderland hospice speaking in a personal capacity, says of assisted suicide requests: ‘When you deal with the things that people are suffering from – loneliness, loss of dignity, loss of autonomy… the number of requests drops precipitously.’ If somebody is suffering, ‘we owe it to them to drill down and work out why’. Giving people lethal drugs instead of care is, he says, ‘like using a hammer to screw in a screw’.

How many cases are beyond the help of palliative medicine? ‘I’ve cared for more than 20,000 people,’ says one doctor who has been medical director at several hospices. ‘I can count on my hands the number who, with the right care and commitment, wanted to end their life.’

Some specialists are less bullish. But they still tend to doubt the legislation will reduce suffering. For one thing, no regulatory authority anywhere has approved any drugs for assisted suicide. Research indicates these drugs may produce serious physical distress.

Already, one in four people dies without the end-of-life care they need. According to the APM’s Sarah Cox, palliative care ‘has improved three times more in countries where assisted dying has not been implemented’. If the new law damages the sector, it could lead to a significant increase in bad deaths.

One possible mitigation would have been an opt-out for hospices and care homes, as in New Zealand and US states with assisted suicide. But Leadbeater feels ‘very strongly’ that assisted suicide ‘shouldn’t be separated from end-of-life care’. MPs have tried to amend the legislation to give hospices the right to set their own binding policies; Leadbeater, repeatedly, has defeated them.

In Canada, one hospice was shut down by the government after refusing to provide assisted suicide. Leadbeater has declined to rule out that happening here. Her Tory right-hand man Kit Malthouse has threatened hospices, saying: ‘Should they still be able to deny what is a legal service, if they are in receipt of public funds?’

In the NHS, says one doctor, culture change tends to be total. That means assisted suicide ‘will be everywhere’

One senior doctor at a London hospice says: ‘I’m not somebody who’d hold up a placard against assisted dying. But this legislation – particularly not allowing hospices to opt out – is a huge deal. Like a lot of hospices we have a neutral stance, and I have colleagues who were pro-the bill. I don’t think they ever thought it would happen here.’’

Not every hospice doctor fears the prospect of an assisted suicide law. One palliative medicine consultant in East Anglia, who supports the bill, argues they should be legally obliged to participate: otherwise ‘there would likely be a majority who object in most hospices, whose voices would win’ and hospices would end up ‘turning their backs on those who want assisted dying’.

Ros Taylor MBE, medical director at Harlington Hospice, believes hospices will ‘rise to the challenge’ and ‘find a way of compassionately and creatively working with this bill, should it pass’.

Some hospices, meanwhile, fear the worst. St Gemma’s in Leeds has said that if NHS funding comes to depend on assisted suicide provision ‘institutions like St Gemma’s may… cease operations entirely’.

The Leicestershire hospice LOROS says it will not provide assisted suicide because ‘none of our senior doctors or nurses would choose to be involved’. The current bill ‘puts us in a challenging situation’, says its medical director, Luke Feathers. ‘While the intent of new AD legislation is to expand choice at the end of life, its impact on hospices could have the opposite effect – reducing choice and access to essential care.’

Few doubt its effect will be far-reaching. Qamar Abbas, medical director at an Essex hospice, says that in the NHS, culture change tends to be total. That means assisted suicide ‘will be everywhere’. Abbas predicts it will become ‘a tick-box exercise’.

In many places the mood is bleak. ‘The fact this has had such a positive response in government,’ says a senior nurse at a hospice in the south of England, ‘makes me want to give up nursing.’ Dr Lee, the Sunderland hospice doctor, is ‘quite frightened’. When MPs first voted for the bill in November, ‘I’ll be honest with you, it was like a bereavement to me’.

‘The fear is really palpable,’ says a consultant at a Yorkshire hospice. ‘I have at the back of my mind what other career roles I could do. It’s heartbreaking.’

Comments