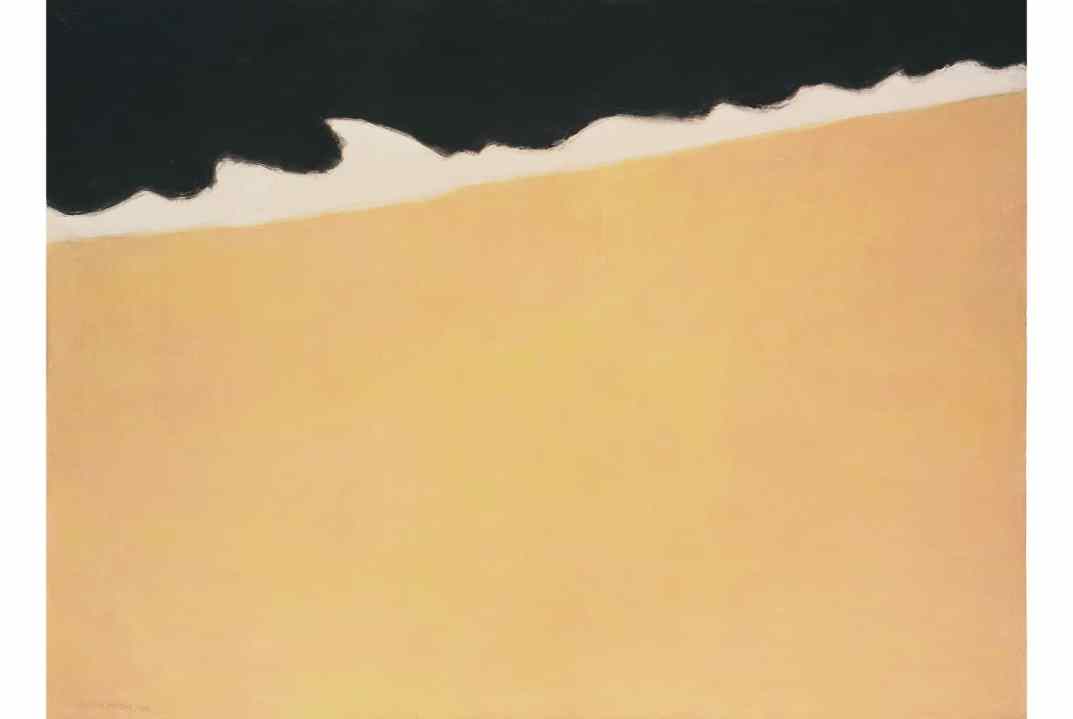

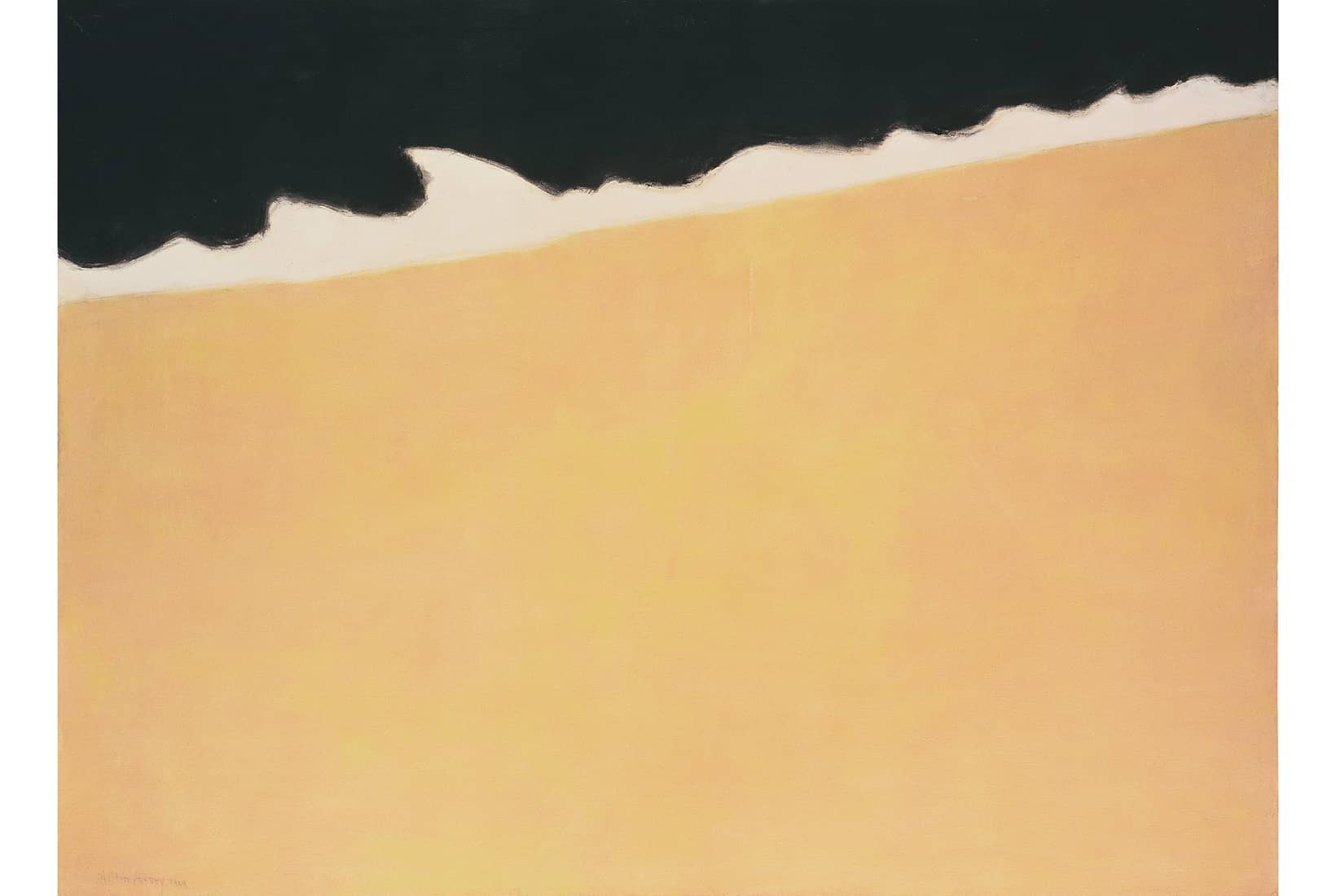

‘I like the way he puts on paint,’ Milton Avery said about Matisse in 1953, but that was as much as he was prepared to say. Contemporary critics tried to ‘pin Matisse’ on him as if art criticism were a branch of police work. He resisted, and remains a slippery customer. Post-impressionist or abstract expressionist? Colour field painter with added figures? To those who view art history as the march of progress towards modernism, he looks like a backslider. Clement Greenberg thought as much, dismissing him in 1943 as ‘a “light” modern who can produce offspring of Marie Laurencin and Matisse that are empty and sweet with nice flat areas of colour…’ Ouch.

‘Light’ is a fair description of Avery’s work: light in tonality, in weight of paint and intellectual baggage. Not a product of the art school system, he assimilated rather than learned his trade. A working-class descendant of English immigrants, he worked in Connecticut factories from the age of 16 and fell into art almost by accident.

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in