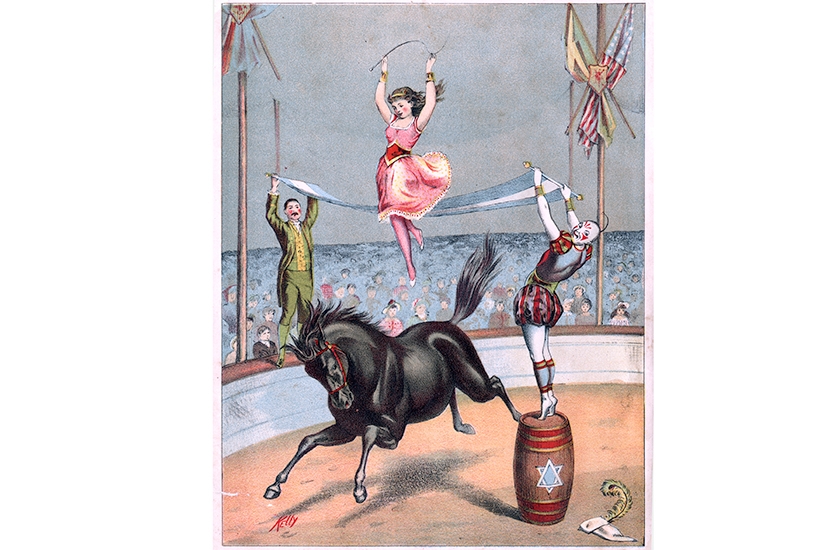

What’s so serious about a red nose? How should we analyse the ‘specific socio-historical relations’ and ‘aesthetic trends particular to geographic context’ of the circus? How can we ‘codify’ equestrian performance in the ring?

With the publication of The Cambridge Companion to the Circus, this artform has tumbled out of the Big Top and into the library and lecture hall. It’s a recent arrival to lofty, learned spaces. When Vanessa Toulmin of Sheffield University, widely regarded as the world’s leading expert on circus and fairground history, first ventured into academia, she did so under the guise of an ‘early film historian’, as circus wasn’t regarded as worthy of study. Now ‘circademia’ has become a respectable area of research for PhD students, and higher education institutes offer degrees in circus studies. Circus has become serious.

Circus has become serious, and there are now degrees in circus studies. Does that wash out the sequinned sparkle?

But does all this analysis and examination wash out the sequinned sparkle? Can circus’s raw joy, derived from visceral pleasure rather than cerebral contemplation, survive such scholarly scrutiny? Unlike other artforms such as ballet and opera, circus has flourished as an outsider, often sniffed at and looked down upon. If it’s brought inside the mainstream artistic canon, does it lose its immediacy and accessibility? Does it dissolve into no more than physical theatre?

I’m a circus person, so naturally greeted this volume of 16 essays from renowned academics worldwide with glee, but also a little bit of worry. Bringing together much of the circus research that’s been quietly happening in archives over the past decade, it is divided into four parts: the international perspective, circus acts, circus today and circademia. Subjects range from the late 18th century, when Philip and Patty Astley founded the first modern circus, in Lambeth, opposite the Houses of Parliament, to today’s contemporary shows.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in