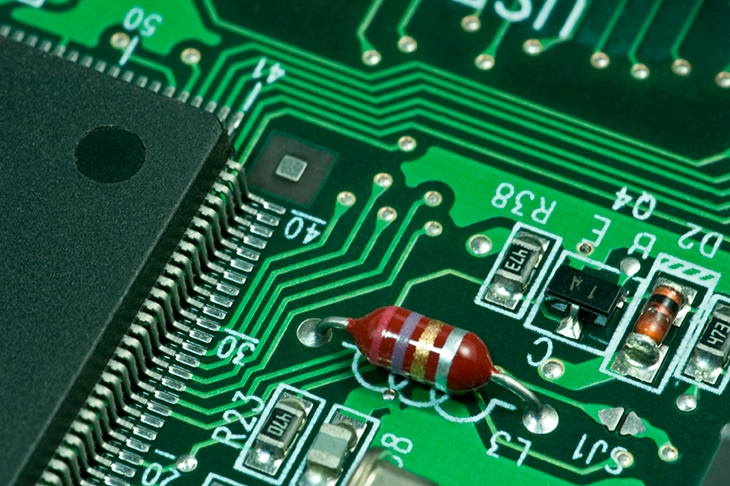

Just as the auto industry embraces the electric future I wrote about last month, it hits a new crisis: a shortage of the microchips that power everything under the bonnet. As a parable of globalisation’s perils, this one has all the ingredients from trade war to fire, drought and Covid pestilence.

When car production slumped last year, chip-makers switched to meet booming demand for parts for smartphones, tablets and laptops. Now car factories are keen to raise output again, but there aren’t enough chips to go round. The leading source, Taiwan, is entangled in US-China tensions and its factories are afflicted by water shortages; other plants have been stricken by fire (in Japan) or extreme cold (Texas). The result is that Ford, Toyota, Volvo and Volkswagen have paused production lines and Nissan’s Sunderland plant has blamed non-delivery of chips for a decision to put 750 workers back on furlough.

Maybe there’s a wider moral here. Cheap labour and just-in-time logistics have accustomed a generation of consumers to miracles of choice and affordability. But now we’re seeing what can go wrong in a supposedly ‘frictionless’ system: trucks gridlocked in Kent, containers stockpiled at the wrong ports, rotting food cargoes, shortages not only of chips but also of minerals needed for electronics, plus vaccine blockades — all point to continuing disruptions and rising costs. Dramatic swings in January’s UK export-import figures were dismissed by some pundits as a Brexit-meets-Covid blip. But they could be the harbinger of an era of fractured trade with ramifications for global prosperity we have yet to discover.

The dignity of ex-PMs

Should former prime ministers ever sully their hands in business? The question arises as the spotlight on the collapse of Greensill Capital swings to David Cameron — whose government appointed the Australian entrepreneur Lex Greensill to ‘sort out the whole supply-chain finance issue for us’ in 2014, and who was in turn hired, after leaving office, as an adviser to Greensill — and rewarded with stock options that might have made him rich if the company had achieved plans for flotation.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in