We hear a lot about the rights of the child, but the first I heard of the child’s right to play was at the Barbican’s latest exhibition. Among the games-related facts in Francis Alÿs’s new show is a quote from Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Children, confirming a child’s right ‘to engage in play and recreational activities’.

Barbie has stood seven times for the US presidency. (As a young looking 65, she could do well)

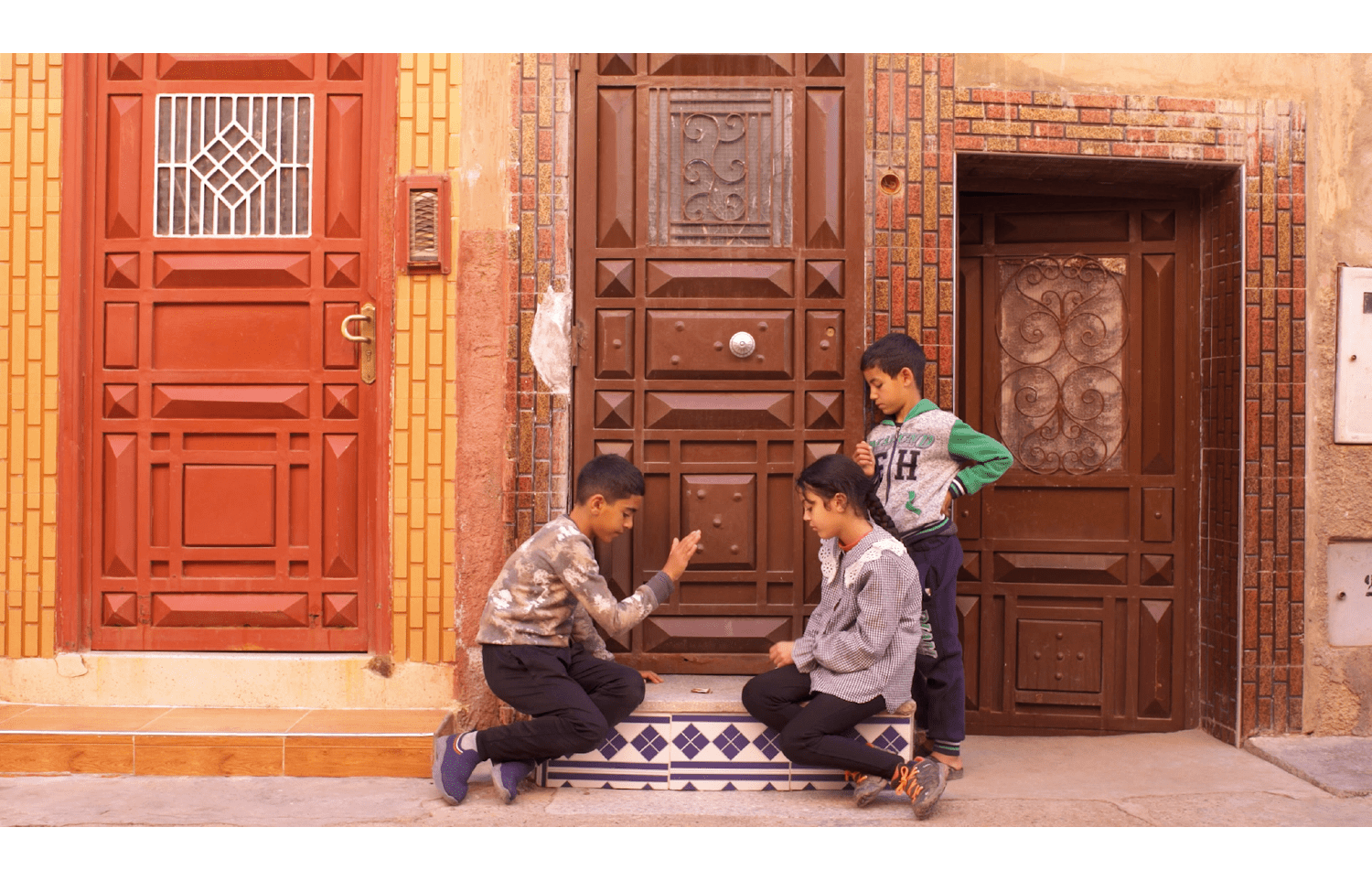

Are children’s games under threat? Alÿs thinks so. Children in Europe today, he laments, have a tenth of the freedom to roam that he enjoyed growing up in the 1960s in a Belgian countryside virtually unchanged since Bruegel. During the course of his travels in 15 countries over the past quarter-century, Alÿs has amassed a cinematic archive of children’s street games. He started in 1999 in Mexico, where he is based, with a boy kicking against the law of gravity by booting a plastic bottle uphill; since then, while filming in conflict zones, he has recorded other forms of youthful resistance. In ‘Haram Football’ (2017) boys in Mosul play a balletic form of air footie in defiance of a Isis ban on ball games; in ‘Parol’ (2023) camo-clad kids patrol the streets of Kharkiv with wooden toy guns in search of Russian spies, stopping drivers at pretend checkpoints to demand passwords, check documents and inspect car boots.

But most of the games in Alÿs’s films are much older: the two girls playing with stones on a Kathmandu stairwell in 2017 are engaged in a version of knucklebones played by royal children on a Hittite relief of 800 bc, while the bicycle tyres driven downhill by boys in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, in 2010 are the descendants of the wooden hoop rolled by the naked youth on a 500 bc red-figure drinking cup from Attica.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in