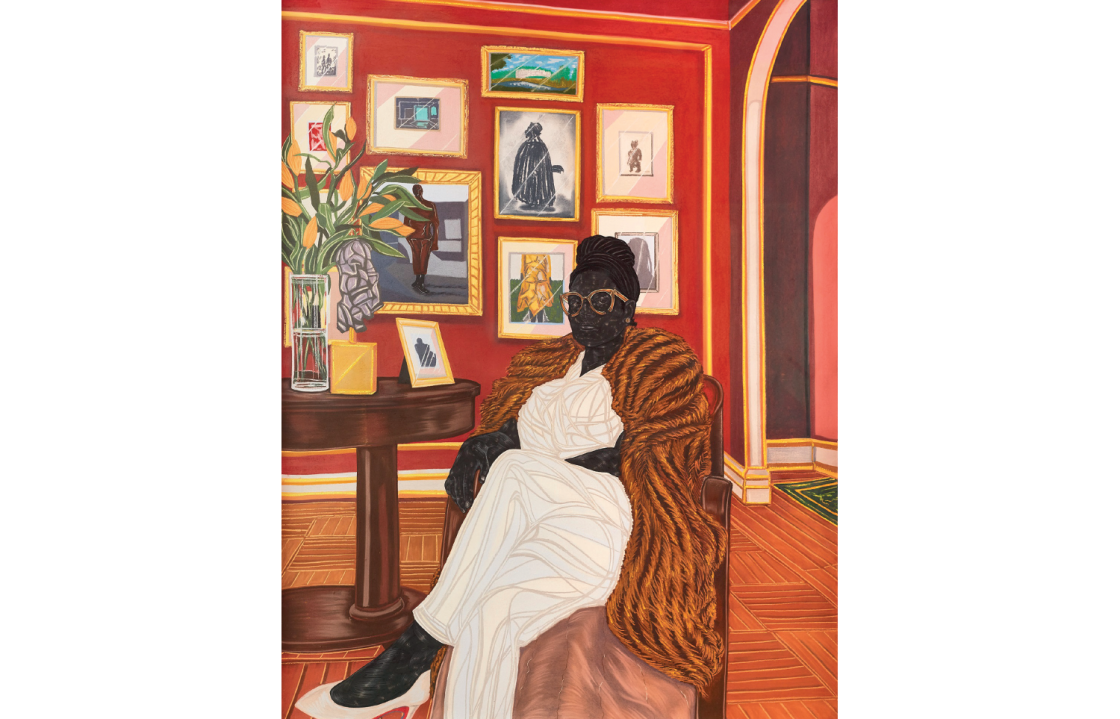

A wave of totalising race-first exhibitions has swept through UK art institutions of late. The National Portrait Gallery’s remit of ‘reflecting’ British society could reasonably make one wary of its turn at the same project. Indeed, a false, stilted language accompanies curator Ekow Eshun’s The Time is Always Now. To have some 20 artists ‘reframing the black figure’ somehow sounds both ambiguous and politically predetermined.

What unites these works is more often a trendy hashtag than ‘lived reality’

Eshun has long been invested in the artistic black diaspora. His 2022 Hayward Gallery show In the Black Fantastic played on fantasy and Afrofuturism and had artists make new worlds that would take over the failing present. This time, however, he resorts to a safe and comfortable cadre of artists, many of whom, like the painter and museum activist Lubaina Himid, have featured in just about every other institution’s race and decoloniality-themed blockbuster. Works by the likes of dub-club abstractionist Denzil Forrester and barbershop-reminiscer Hurvin Anderson, who rose to prominence between earlier waves of interest in black creativity, mix with images by celebrated American chroniclers of urban life Henry Taylor and Jordan Casteel.

These are steady hands, and Eshun does little to challenge their aesthetic conservatism. He does even less to challenge the institution’s racial platitudes. In parts of the show, skin colour is a painter’s superpower – in others, the root of historical trauma. The gallery thinks nothing of bridging continents yet turns a blind eye to social class. It’s not clear if it’s the artists or the viewers who are expected to believe these contradictions.

One way to evaluate this proposition is to consider the sociological and material claims made by the museum on behalf of the art. Under such scrutiny, what unites these works by Brits, Kenyans, and Americans is more often a trendy hashtag than the ‘lived reality’ to which Eshun appeals.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in