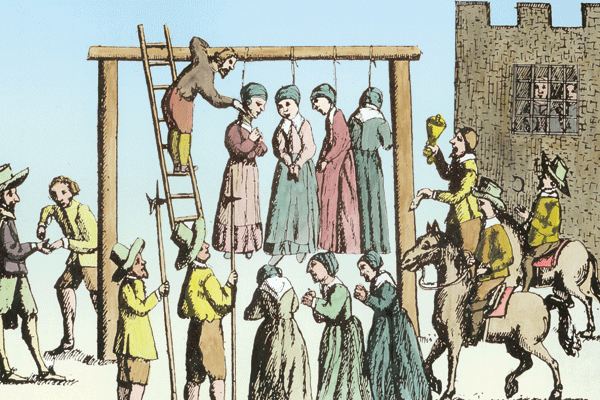

It is not a criticism of Philip Almond that The Lancashire Witches, published to mark the 400th anniversary of the Pendle witch trials, is a depressing read. On the contrary, Almond has produced a fine and lively study of the events in 1612 when eight women and two men were tried for witchcraft.

What is depressing is how ordinary those involved seem to be. This is not a story of gothic horror or bizarre group psychosis. It is a tale of people being caught out for doing relatively ordinary things.

The Pendle witches were not members of some pagan or Wiccan cult, or even genuine devil-worshippers. As Almond makes clear, much of the folklore and superstition that came to be called witchcraft had previously been part of life. Consequently the supposed witches were really members of a typical rural community subject to the machinations of outsiders keen to make a name for themselves.

The catalyst for this was the arrival of James I on to the English throne. James brought with him a Scottish credulity towards witchcraft at odds with the more tolerant English tradition. He even wrote a book on the subject, called Daemonologie. As Almond explains, judges like Edward Bromley and James Altham, who heard the Pendle cases, curried favour with the king by trying to weed out witchcraft. In looking for it so vehemently they found it in abundance.

In Pendle their agent for this was a Puritan preacher called Roger Nowell. He was a notorious witch-hunter who falsely promised leniency to those he accused if they in turn accused others. But at the centre of Almond’s book is the court clerk in Lancaster, Thomas Potts, who was commissioned by Bromley and Altham to publish the Pendle witch trials as a book.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in