In 1299, Amatino Manucci, a Florentine helping to run a merchant’s business in Provence, kept at least seven ledgers and notebooks, each serving a specific purpose. One covered the firm’s trade in wool and cloth, another in wheat, barley and other victuals, and so on. It wasn’t just figures Manucci worked with. It was also financial concepts, quite advanced by the standards of that time: accounting entities and periods, profit and depreciation – notions that heralded the invention of accounting as we know it. ‘If you’ve ever tapped numbers into an Excel grid,’ Roland Allen writes in his engaging popular history, ‘you have Manucci and his contemporaries to thank – or blame.’

‘Take a note in a little book that you should always carry with you, preserved with great care’

Allen considers the notebook in its various forms, from the wax tablet to the electronic spreadsheet, and from early modernity to the present day. Why, despite the digitisation of everything, do many of us still choose to write and draw on paper? This question is constantly on Allen’s mind as he makes forays into art and science, self-help and politics, tracing the relationship between power and information technology over the centuries. His research is based on a variety of primary and secondary sources; his writing has the lightness of touch needed to turn the dry pages of notebooks into living historical documents.

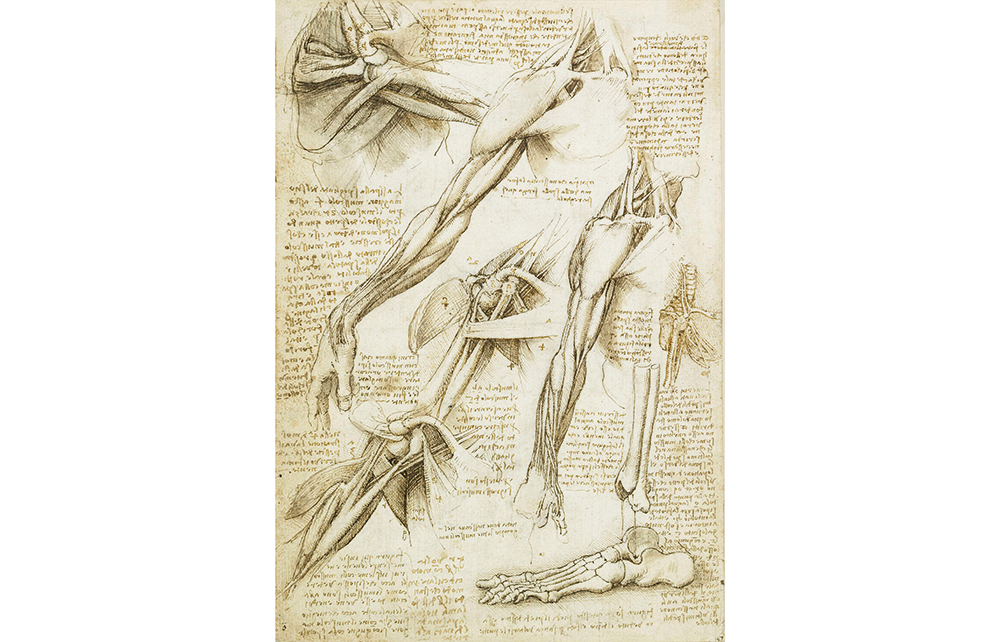

Italy is often in the focus: Florence, Venice, Genoa – places whose natives once dominated European trade. These agents of progress developed much more than sophisticated book-keeping techniques. We visit the Italy of Leonardo da Vinci, who advised his fellow artists to ‘take a note…with slight strokes in a little book that you should always carry with you… preserved with great care’, and of Marco Polo, whose account of his travels, Il milione (a word he coined, according to a legend, to describe a very large number), was often excerpted in zibaldoni, Florentine personal anthologies popular in the 14th and 15th centuries.

From Renaissance Italy we travel to northern Europe, whose inhabitants kept ‘friendship books’ for their acquaintances to leave epigrams and signatures in.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in