The principal purpose of Captain James Cook’s last voyage, which began in Plymouth on 12 July 1776, was to discover the elusive Northwest Passage. Attempts had been made before, in vain, from the Atlantic, but this time it would be from the west, from the Pacific.

On the way, Cook was to return an Anglicised Polynesian named Mai to Raiatea, ‘a ragged volcanic island’ about 130 miles north west of Tahiti. Mai takes up much of Hampton Sides’s narrative, offering ‘a poignant allegory of first contact’, before being deposited home with his cargo of English domestic farm animals and his suits.

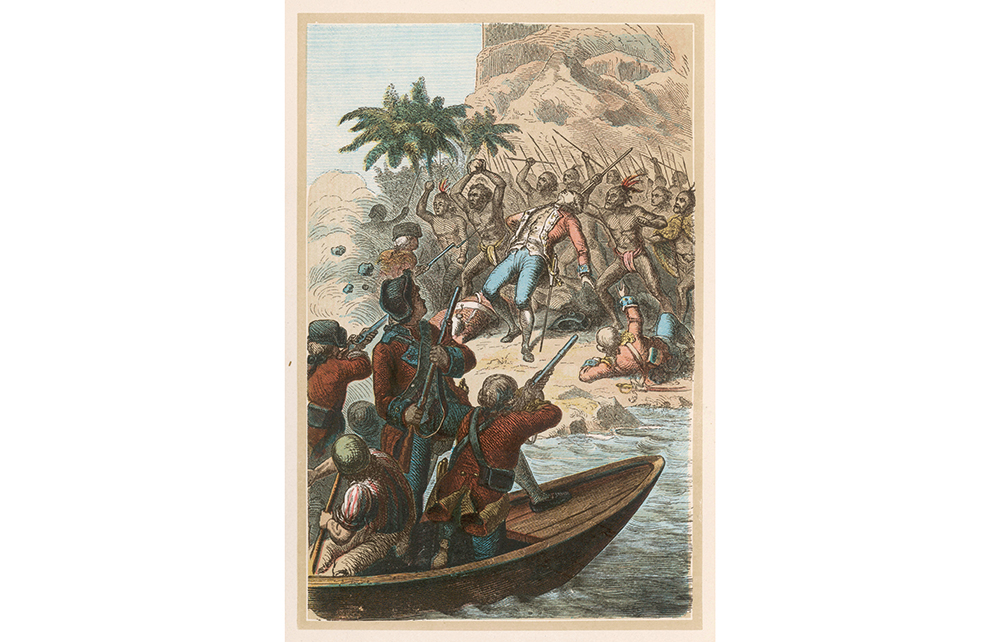

Prior to that, Cook had investigated, in New Zealand, the massacre of ten crew members of the Adventure, the Resolution’s sister ship on his previous voyage. His attitude to this tells us much about him. He was neither vengeful nor judgmental. One of his powering characteristics was a profound curiosity. He wanted to know what had happened. In the event, he decided that the Maoris had been provoked. Despite the victims having been eaten, Cook knew anthropophagy was a Maori warrior ritual. The custom, he wrote, has ‘undoubtedly been handed down to them from the earliest times’. He saw no reason to impose Christian morality or English ethics.

Cook’s moods on this third voyage were regarded by those who knew him as more friable than before. He lost his temper easily and had crew members thrashed frequently for minor misdemeanours. Errors of judgment crept in where once he had always seemed right. Explanations for his caprices have ranged from a parasitic infection after eating bad fish to sciatica and consequent opioid addiction, and vitamin B deficiency. Or he may just have been getting old and crotchety, having spent so much of his life at sea.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in