Canadians, like the English, are known for our tendency to apologise. The difference is, we actually mean it. Our modesty is not false. Our inferiority complex is not a polite, self-deprecating joke. We really do feel inferior. And we really are sorry. Sorry for taking up so much space for so few people. Sorry for being so dull and functional compared with our glitzy neighbour to the south. Sorry about Celine Dion. And above all, sorry for failing to produce much of anything great apart from Niagara Falls and the Rockies, which we can’t take credit for anyway.

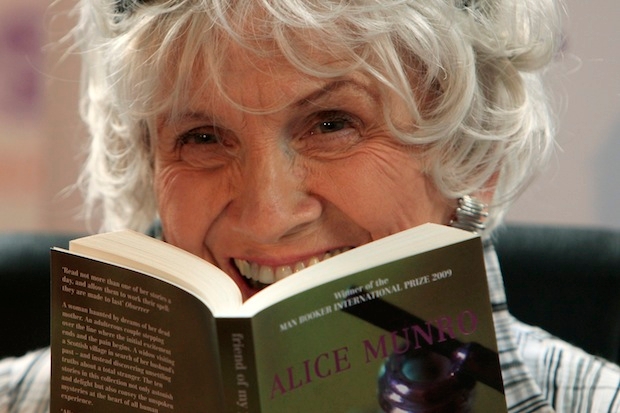

So when Alice Munro, our most quietly adored author, was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature last week, the entire nation gave a collective whoop and then glanced furtively over our shoulder as if to say, ‘Are you sure there hasn’t been some mistake?’

Munro is the most unlikely of Nobel laureates. Her body of work consists almost exclusively of short stories set in small towns about the lives of middle-class Canadians. Her prose style is restrained. Her subject matter grounded in the real. Divorce is a big theme. As is adultery. Tall poppy syndrome, as evidenced in the title story of her 1978 collection Who Do You Think You Are?, is another persistent obsession. Not surprisingly, Munro has mixed feelings about her own literary fame, which is why she rarely gives interviews or travels from her home in Clinton, Ontario. This is not to say she’s a reclusive bumpkin — the literary love child of Thomas Pynchon and Jill Archer — as some media outlets have portrayed her. Just that she is uncomfortable with notions of greatness, especially her own.

As she told Maclean’s magazine in the 1990s, ‘In my family, as in Canada, there was a double message. If you don’t get to be famous, then the attitude was, “Well, how come?” And if you do become famous — “Well, how come?” ’

But for all her modesty, Munro does manage to offend some people. When her win was announced the novelist-turned-screenwriter Bret Easton Ellis tweeted that Munro was ‘overrated’ and the Nobel was now ‘officially a joke’. (Harsh words coming from a man whose last film starred Lindsay Lohan and the porn star James Deen.) And earlier this year in the London Review of Books, the American writer Christian Lorentzen spent several thousand words ripping apart the ‘confusing consensus’ around Munro. This phenomenon, he writes, ‘has to do with the way her critics begin by asserting her goodness, her greatness, her majorness or her bestness, and then quickly adopt a defensive tone, instructing us in ways of seeing as virtues the many things about her writing that might be considered -shortcomings.’

In Lorentzen’s view, most of Munro’s shortcomings are all down to the narrowness of her subject matter. Subject matter so grim and unglamorous it induces in him ‘a state of mental torpor that spread into the rest of my life. I became sad, like her characters, and like them I got sadder… I saw everyone heading towards cancer, or a case of dementia that would rob them of the memories of the little adulteries they’d probably committed and must have spent their whole lives thinking about.’

But Munro has always been easy to mock in this way. And she has never been particularly popular with sarcastic young men. When I was in school, I remember the cool boys in my English class came up with a nickname for her collection of linked stories, Lives of Girls and Women, which is mandatory reading in Canadian high schools. ‘Lives of Sluts and Whores’, they called it, on account of its cover featuring a photo of two girls in cardigans lying together in a field (lesbian lovers perhaps?). But for me, a nerdy, Wasp-y smalltown child of divorce, encountering Munro’s characters was like meeting people I had always known but somehow just barely remembered. Her ability to illuminate the finer details of everyday life — to subtly reveal not just what people do, but why they do it — was a revelation. Reading Munro was like re-encountering everyday life with supernaturally heightened powers of insight. Her stories were less about event and more about emotional revelation. Like life itself, they were both astonishingly complicated and profoundly simple at the same time.

Years later, when I read Flaubert’s declared ambition to write a book about nothing — ‘a book without exterior attachments, which would be held together by the inner force of its style, as the earth without support is held in the air’ — I immediately thought of Munro. This is exactly what she has done, though not quite the way Flaubert intended it, and it is why the Nobel committee were revolutionary to select her. Has there ever been a more controversially uncontroversial Nobel laureate? Not that I can think of.

Her subject matter is neither sweeping nor broad nor political. She has no particular agenda or world vision. Unlike Margaret Atwood, who until last week seemed -Canada’s best Nobel bet, Munro is not interested in futuristic dystopias, feminist science fiction or environmental warnings. She is concerned only with human behaviour and emotional truth. As the writer Sheila Heti put it in the New Yorker last week, ‘She just goes straight to what matters most… There is nothing else.’

Because her genius is her simplicity, there is a tendency to characterise Munro as unsophisticated, which of course she is not. Yes, she found out about winning the Nobel from a voicemail on her landline (her friend Atwood kept tweeting her to ‘pick up the phone’ — a useless exercise since Alice Munro is obviously not on Twitter) but she is no rube. In her interviews, she was articulate and gracious and clearly delighted to win, but the fact is this brass ring will probably not change her life one iota. Like the people in her stories — and Canadians in general — Alice Munro is wary of glory. I imagine her Nobel sitting on a kitchen shelf beside a jar of blanched almonds and a dusty old Booker. So she will stay in her hometown and take long walks and quietly contemplate the intricate emotional complications of life. She is retired and famous now you see. And probably asking herself, ‘Well, how come?’

Comments