Back home from a week in Italy, I almost feel that I haven’t left. For I go almost at once to Milton Keynes to see Donizetti’s quintessentially Italian opera, L’elisir d’amore. It is a superb, joyous production by the Glyndebourne Tour company, one of which any great international opera house would have been proud. And here it is being performed in Milton Keynes, not a town generally associated with cultural sophistication. But then ‘Das Land ohne Musik’, as England was once cruelly called by a German music scholar, is now awash with opera. It has been spread across the land by country opera festivals, springing up everywhere in imitation of Glyndebourne, and by opera touring companies penetrating even the least-favoured parts of the country (among which I don’t, of course, include the booming city of Milton Keynes). And thanks to Benjamin Britten, whose centenary is being celebrated this year, they even put on operas that are actually English.

This year I have been to more operas than I have for ages. I saw Wagner’s Ring at Longborough in Gloucestershire, his Parsifal at the Proms, and Britten’s Peter Grimes on the beach at Aldeburgh in Suffolk. I also saw a stunning performance of Richard Strauss’s Elektra at the Royal Opera House. And then to make up for the greater attention paid to Wagner than to Verdi in their joint bicentenary year, I went to four Verdi operas at the ROH: Rigoletto, Otello, Simon Boccanegra, and Les Vêpres Siciliennes. I am left feeling rather amazed by the high quality of almost all these performances. If England could once be dismissed as a country without music, it hardly can be any more.

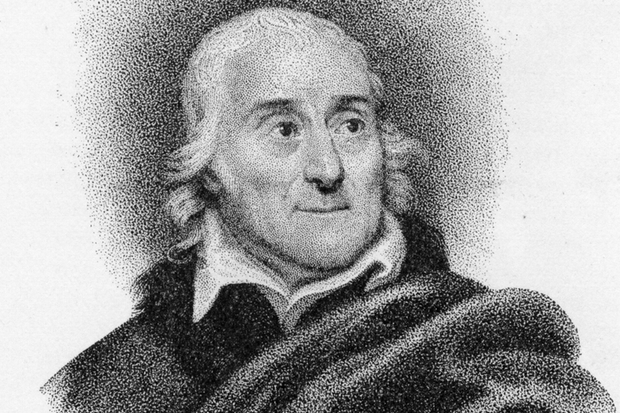

In Italy I read Anthony Holden’s biography of Lorenzo Da Ponte, the Italian poet and author of 28 opera libretti, whose life was so weird and chaotic as to be hardly believable.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in