Wherever one looked in the arts scene of the 1940s and ’50s, one was likely to encounter the tragicomic figure of John Minton. Whether he was dancing to the trad jazz of his pupil Humphrey Lyttelton — who recalled his style on the floor as ‘formidable and dangerous’ — or drinking at the Colony Room where Francis Bacon once poured champagne over his head, the painter and illustrator was ubiquitous.

Even if he never produced a great picture, Minton deserves the exhibition at Pallant House, Chichester, marking the centenary of his birth, and the fine accompanying book by Frances Spalding and Simon Martin. In its way, failure can be as interesting as success, as well as more poignant.

When asked what was the greatest difficulty he had encountered as an artist, Minton replied, ‘Instant recognition at an early age.’ He was one of a small group of painters, often dubbed neo-romantics, who came to prominence during the war.

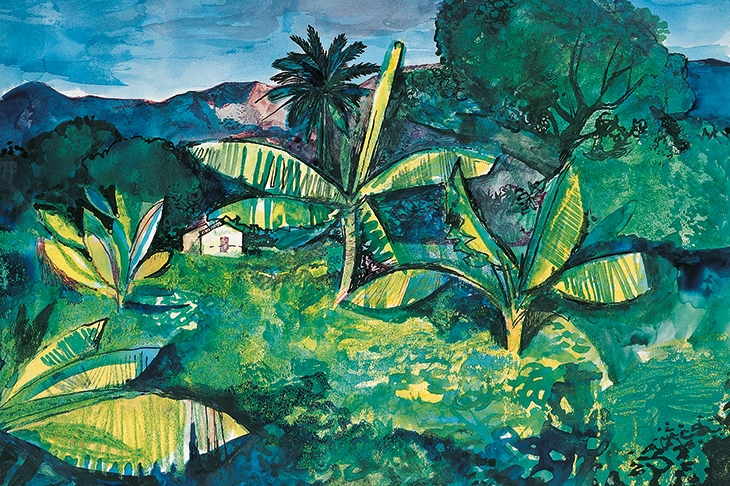

Minton’s melancholy views of bombed-out ruins struck a chord in the dark years that followed the Blitz, as did the pastoral scenes in an idiom borrowed from Samuel Palmer that offered refuge in a poetic past. After 1945, his art provided a different sort of escape from dismal post-war Britain. He produced a stream of book illustrations of hot, exotic places: Corsica, Morocco, Jamaica.

Elizabeth David was delighted with the jacket design for her Book of Mediterranean Food, enthusiastically describing its panorama of ‘tables spread with white cloths and bright fruit, bowls of pasta and rice, a lobster, pitchers and jugs and bottles of wine’ and a ‘brilliant blue Mediterranean bay’ beyond. This was a dream of warmth and plenty in an era of rationing.

Perhaps it was too much of a dream (David decided to opt for more earthy illustrations of vegetables for her later Italian Food).

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in