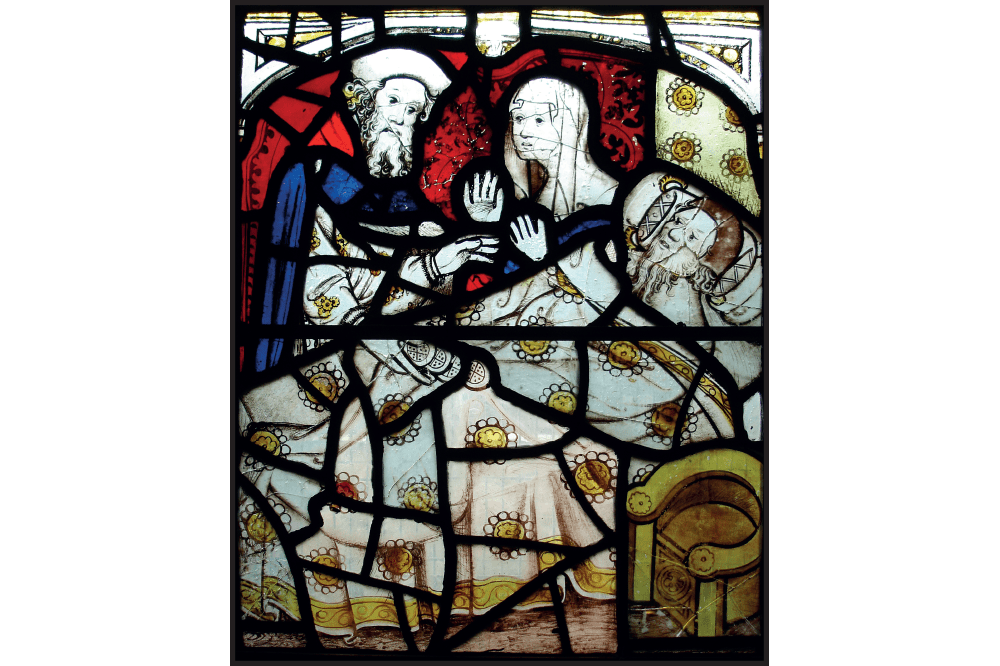

On 13 December 1643, a Puritan minister called Richard Culmer borrowed the Canterbury town ladder and carefully leaned it against the Cathedral’s Royal Window. He then ascended the ladder’s 60-odd rungs, holding a pike; according to his account, modestly written in the third person, ‘Some people wished he might break his neck.’ Culmer had in his sights the ‘wholly superstitious’ depictions of the Holy Trinity, of ‘popish saints’ such as St George, and in particular of St Thomas Becket. There Culmer perched, he recalled cheerfully, ‘rattling down proud Becket’s glassy bones’.

‘Our lives are like broken bits of glass, sadly or brightly coloured, jostled about and shaken’

Culmer thus earned a place in the stained-glass hall of shame alongside Henry VIII, who set the precedent by smashing up Becket’s shrine in 1538; Edward VI, who icily decreed in 1549 that allegedly superstitious images should be ‘defaced and destroyed’; and many of Culmer’s fellow puritans, who wreaked havoc in the 1640s. But it also includes people like the architect James Wyatt who, when restoring Salisbury Cathedral in the 1790s, sold off much of the medieval glass because he didn’t see the point of it. By the 19th century, stained glass – especially in Britain – was a kind of lost art needing to be revived. Which, wonderfully enough, it was. Stained glass as a church decoration goes back to at least the 7th century, when – not for the last time – an English churchman hired continental artisans to do a proper job of glazing his windows. The turning-point, though, was the invention of the gothic style. When Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis worked out how to combine the flying buttress and the rib vault, cathedrals no longer needed to be built so solidly. They could stay standing even with huge expanses of window, which could be filled with almost absurdly elaborate creations.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in