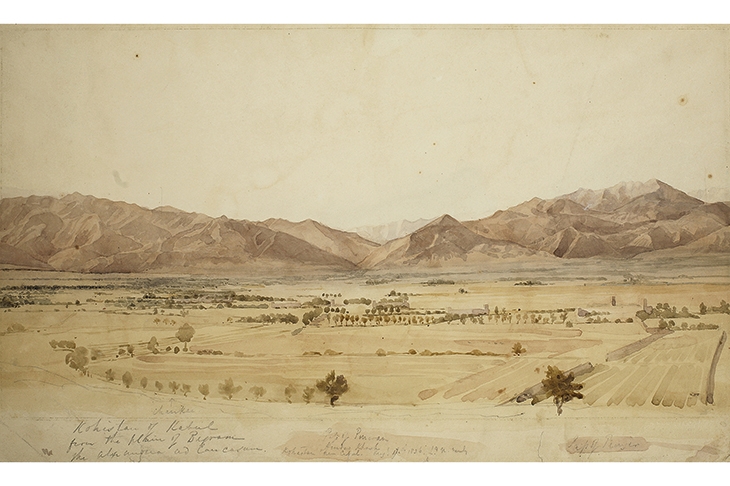

‘Everyone knows the Alexandria in Egypt,’ writes Edmund Richardson, ‘but there were over a dozen more Alexandrias scattered across Alexander the Great’s empire.’ By the early 19th century, though, very few had been identified. Moreover, the prevailing scholarly view was that there remained ‘not a single architectural monument of the Macedonian conquests in India’ — let alone in Afghanistan, which had, ‘for more than 1,000 years… been a blank space in western knowledge’. So finding one would be ‘a world-changing achievement’.

At dawn on 4 July 1827, Private James Lewis of the East India Company’s Bengal artillery walked out of the Agra fort and into history — or at any rate into some amply trodden historical terrain. Not that he knew it. An intelligent but poor enlister from the ‘fetid’ heart of London, he’d spent six sweltering summers watching the officer class get rich, and frankly he’d had enough. ‘This is a story about following your dreams,’ says Richardson; but ‘had he known what was coming, Lewis might have stayed in bed’.

For one thing, he was now on the run, highly visible and unacquainted with the languages of India and the cholera-ridden countryside. For another, he was destitute. The only good news was that it was too hot for tigers. He emerged out of the Thar desert, at Ahmedpur (in present Pakistan), a changed man — starting with his name, which was now ‘Charles Masson’.

Like any half-decent adventurer, Charles Masson read his own obituary at least once

He was neither an especially hardy traveller nor a brilliant linguist, but he discovered two crucial things about himself: a capacity for fleshing out the bare bones of the truth (not least in order to tell people what they wanted to hear), and an increasing passion for Afghan history and the travels of Alexander the Great.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in