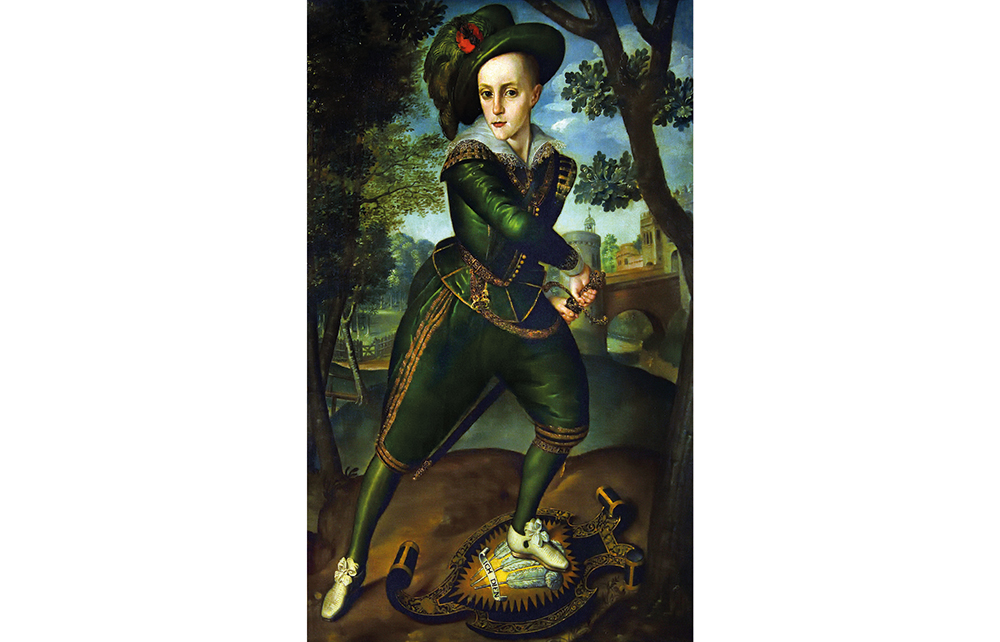

Four years ago Roy Strong – one-time director of both the National Portrait Gallery (1967-73) and the V&A (1973-87) – published The Elizabethan Image: An Introduction to English Portraiture, 1558-1603, in which he returned, after more than a 30-year hiatus, to the subject with which he first made his name: the imagery of Queen Elizabeth I and her court. Now 88, the indefatigable Strong has produced a follow-up volume charting the fate of portraiture (and painting and the visual image more generally) at the courts of Elizabeth’s Stuart successors, James I and Charles I.

Charles I would travel by barge to Van Dyck’s studio to pass the time with him and watch him paint

The format of – and thinking behind – The Stuart Image is the same as in the previous book. Strong has revisited his own landmark research from the 1960s to the 1980s and knitted it together with the findings of subsequent generations of art historians to create an accessible, jargon-free introductory text for the general reader. Most scholars of the Stuart court and its imagery have tended to tackle the subject via the leading painters of the day: Rubens, Van Dyck and so forth. Strong, by contrast, takes the leading patrons of the day – the Stuart kings, their consorts, and their courtiers – as his point of departure. It is an approach which – coupled with his keen eye for the amusing and telling anecdote – makes for a narrative that zips along.

We meet courtier-collectors, such as James Hamilton, 3rd Marquess of Hamilton, who acquired more than 600 Venetian and north Italian pictures in a short space of time in the 1630s. In these endeavours he was assisted by Basil Feilding, 2nd Earl of Denbigh, the English ambassador to Venice, whom he pressed into service as his agent.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in