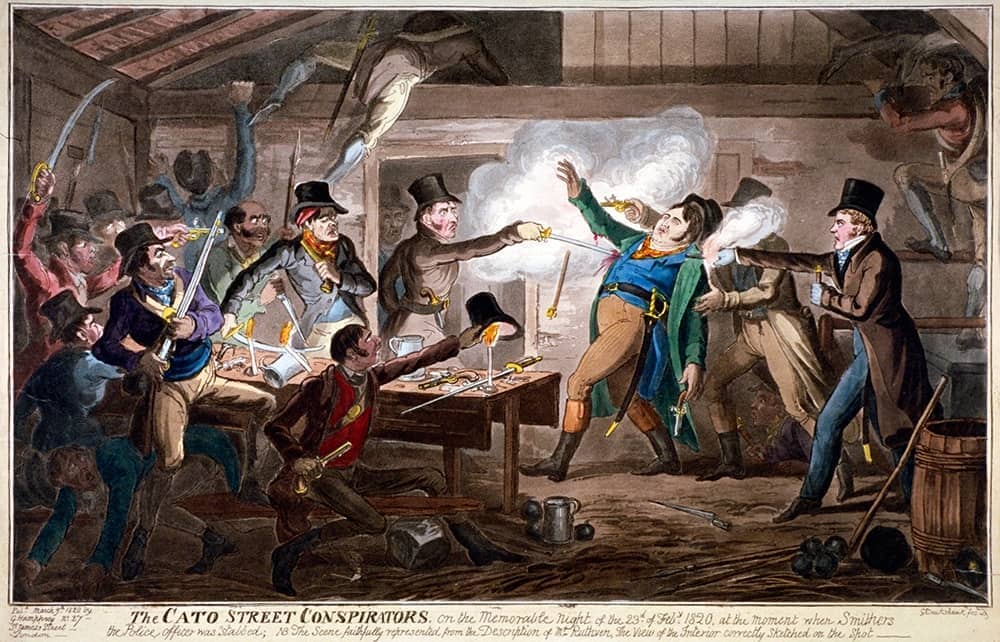

Almost half of the terrorists hadn’t even turned up. Still, on the night of 23 February 1820, 25 men, including a butcher, several shoemakers and a cabinet maker, met in a hayloft on Cato Street, just off the Edgware Road in central London. Led by the semi-respectable son of a tenant farmer, Arthur Thistlewood, their plan was to assassinate the prime minister Lord Liverpool and his cabinet, who were thought to be dining together at the Grosvenor Square mansion of Lord Harrowby, the president of the privy council. The butcher, James Ings, would decapitate everyone at the table, putting the severed heads of Lord Castlereagh and Viscount Sidmouth (foreign and home secretary, respectively) into two bags before impaling them on pikes and parading them through the streets as artisanal revolution was unleashed. Except it didn’t quite work out like that.

This was because the cabinet dinner was a set-up provoked by an impoverished government spy, George Edwards, who had infiltrated the conspirators’ ranks; in the event, the authorities intercepted most of the insurgents at the hayloft and within three months had executed five of them and transported another five to Australia.

They planned to decapitate the entire cabinet at dinner, and parade two heads on pikes through the streets

Vic Gatrell’s terrific new book is the richest account of the Cato Street conspiracy ever written. He provides a gripping contextualisation of the events which led up to and ensued from that strange night in a shabby London stable, using spy reports, trial transcriptions, maps and, most impressively of all, dozens of contemporary prints, paintings and sketches. Historians of all stripes have, up until its bicentenary in 2020, given the conspiracy relatively short shrift, often treating it as a historical dead end – an anti-climactic interlude which, in its very failure, says little about the progress of parliamentary reform, the emergence of the labour movement, or the making of the working class.

Gatrell, however, recovers the contradictory reactions of horror and sympathy felt by contemporaries, enjoining his readers to regard the conspiracy as ‘underdog history at its purest’. He demands that we acknowledge the extremities of hunger, poverty and illness that drove the ultras’ desires to topple Lord Liverpool’s government in the wake of the Peterloo massacre of August 1819, which saw a yeoman cavalry kill 18 (including four women and a two-year-old boy) and injure 670 for protesting in favour of universal suffrage.

If Gatrell succeeds in his aim of establishing ‘a human connection with the poor people’ whose lives animate his narrative, he steadfastly refuses to photoshop the conspirators into titanic labouring heroes, selflessly carrying the torch of liberty for humankind. Justified as their desire for revolution might have been, the ringleader Thistlewood and one accomplice especially, the Jamaican cabinet maker William Davidson, frequently emerge from this book as manipulative, unpredictable and untrustworthy.

These are qualities they share with the book’s principal villain, Lord Castlereagh, a statesman who, in his indifference to human suffering, is shown to be fully deserving of the mock epitaph that Lord Byron composed for him and sent to Thomas Moore in the weeks before the events at Cato Street: ‘Posterity will ne’er survey / A nobler grave than this: / Here lie the bones of Castlereagh:/ Stop, traveller, and piss.’ Byron, it should be remembered, was also contemptuous of the Cato Street men as ‘desperate fools’, doubting ‘the virtue of any principle or politics which can be embraced by similar ragamuffins’.

Gatrell has us survey the lives and sufferings of the conspirators and their families in a very different spirit. It is hard not to feel for the Scottish cobbler James Gilchrist, who was put on trial for his life but had his death sentence respited in part because of his tearful account to the court of his motivation for joining in with the plotters: ‘I was not a man that suffered myself to be among radicals, but I had nothing to eat… and when I went upstairs [with the conspirators], in a very little time came in bread and cheese.’ Likewise, with the wives of the five executed men: they petitioned for the return of their husbands’ bodies, hoping to display the decapitated, mangled corpses to a paying public ‘for the benefit of the poor families, who are literally starving’. When their request was declined by Viscount Sidmouth, the women mounted a public appeal for subscriptions to relieve them and their children from ‘famine and despair’.

However deluded, disorganised, hungry, impetuous, mentally ill or murderously violent the various Cato Street conspirators might have been, Gatrell’s final assessment is that they were ultimately undone by a political system which promoted aristocratic men who had little feeling for the poverty of the most vulnerable members of the society they governed. If the radicals were cynically manipulated by the Regency regime, that regime was profoundly insecure and frightened of a class of people it didn’t much care to understand.

Comments